Tiffany Savage and Lynde Griggs are co-founders of Belle & Sparrows, a “by women for women” nonprofit seeking to stand in the gap for marginalized women in North Texas and around the world. Both women, while on separate mission trips, realized the need for others to advocate on behalf of women and children who are victimized through abuse and trafficking. In teaching women about their God-given worth, Savage and Griggs now take other women on mission trips and teach victimized women important life skills for success outside abusive relationships.

The following is an interview with Savage, the granddaughter of a Baptist preacher and church planter. She was raised in a Southern Baptist church and served a Baptist church for several years. Belle & Sparrows, the organization she co-founded with Griggs, is intentionally nondenominational.

Though we don’t want to acknowledge it, women and girls face two particular problems: sex trafficking and domestic violence. This is not only a global problem; it is also a local problem. Just how many girls experience sex trafficking in North Texas?

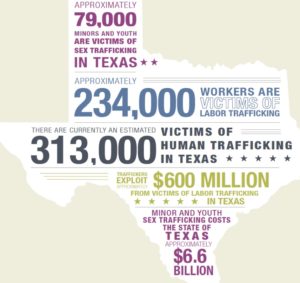

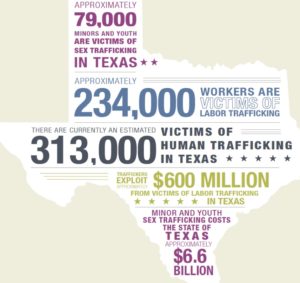

There are about 400 girls being trafficked on the streets of Dallas each night with their average age being 13 years old. “On the streets” means girls are literally placed on street corners, stadium parking lots and similar locations around the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex.

In addition to sex trafficking of women and girls, how many women in the DFW Metroplex face domestic violence?

In the DFW Metroplex, I have stats from 2013, and the numbers have increased since then.

In 2013, the Dallas Police Department Family Violence Unit reported 13,007 family violence calls resulting in 1,215 aggravated assaults, 23 murders, 10,812 reported offenses, 91 sexual assault offenses, 180 violations of protective orders and 5,782 arrests.

- As a result of domestic violence, 246 women go to shelters in the Metroplex each night with many others being turned away for lack of space.

- One in four women faces domestic abuse from a partner.

- A woman is beaten every nine seconds in the United States and 15 calls a minute are made to hotlines for domestic violence.

And that’s just the DFW Metroplex. Do you have statistics for some other places in Texas?

Last year, the state of Texas served more than 70,000 families in family violence programs. Texas family violence programs received 172,573 hotline calls in 2016. The National Domestic Violence Hotline received 16,045 calls and 1,206 chat requests from Texas in 2016.

How does sex trafficking tie into addiction, domestic violence, and incarceration?

How does sex trafficking tie into addiction, domestic violence, and incarceration?

The U.S. State Department showed that “almost 70 percent of adult female trafficking victims experienced domestic violence prior to being trafficked.”

If a drug-addicted parent loses his or her job and other supports, he or she can spiral downward into addiction. With nothing left to sell or steal, the addict often decides to sell his or her partner—or child—for drugs or money.

Oftentimes, a girl falls into the trap of a trafficker, and before she finds her voice, he has her addicted to drugs so she can’t leave because she has to fuel her addiction.

Domestic violence can lead to drug use, and drug use can lead to prostitution, and prostitution often leads to incarceration or trafficking. Jails and prisons are becoming the new hunting grounds for traffickers. As soon as women are arrested and charged, they are becoming targets for human traffickers. Grooming begins with letters once they are targeted.

What is grooming, and what does it look like in the context of trafficking?

Grooming takes place when sex traffickers target vulnerable women, girls and boys and then execute a psychological and physical grooming process aimed at transitioning them to a dependent role. Using violence, substance abuse, false promises and manipulation, traffickers then abuse the dependency and soon have physical and mental control over their victims.

You alluded to a woman’s need for financial stability and the promises traffickers make to that provide that. What is the relationship between a woman’s ability to earn a fair wage and the likelihood of her being trafficked?

Trafficking victims are lured by false promises of decent jobs and better lives. The inequalities women face in status and opportunity worldwide make women particularly vulnerable to trafficking. If a woman cannot earn a fair and equitable wage, she often feels trapped with no other choice but to follow the lead of a trafficker.

Why can’t women make a fair wage to feed, clothe and provide housing for themselves and their children?

Women in the U.S. who are faced with being abused, who have come out of a violent relationship, who have been incarcerated previously or who are trying to overcome addiction struggle to find jobs that afford them a wage to provide for themselves and their children.

Minimum wage jobs or jobs that will hire someone with a record will not be enough to sustain a family of more than one. This leaves a mom with undesirable options, but when backed in a corner, she will do whatever it takes to feed and clothe her children.

Clearly, there is a need for advocacy for vulnerable women and children. Since there are already governmental initiatives underway, is there a need in North Texas for a nonprofit organization that empowers marginalized women?

There are many local organizations doing great things; however, there still seems to be a gap when it comes to empowering women to feel accomplished and worthy as women by learning a trade or skill and also giving them a decent wage for the work they do.

This is where Belle & Sparrows comes in. We seek to fill this gap by helping with economic sustainability, social justice and social enterprise.

We want to help more women find and act on opportunities to start and maintain small businesses with earning potential for their families.

We want to see the message of worthiness repeated in as many places and to as many people as the Lord will allow. The hope that is sparked by the message of worthiness can flourish into a flame for these women and for their generations to come!

I’m intrigued by this “message of worthiness.” Where does that idea come from?

God says very clearly several times in his word that he even cares for a tiny sparrow. How much more important or “worthy” of his love are we?

We are called to be image bearers of Christ. The more you believe you have inherent value and something important to contribute to the world, the more confidently you can move into your calling!

This is hard to grasp for many women who have faced abuse, addiction, incarceration, etc. Failing to believe these truths is often a result of a deeply rooted sense of inadequacy. To fight against these lies, we need to remind women of these truths of worthiness!

Churches may think trafficking doesn’t affect them. What are churches missing, and what can they do to help?

There are girls sitting in church pews each Sunday who are being trafficked by their boyfriends the other six days of the week. Often times church is the only place traffickers will let their girls go unsupervised.

How can the local church be the hands and feet of Jesus Christ if we aren’t being his eyes and ears, too? How can we love someone if we don’t even know they exist? Fighting human trafficking can begin with an act as simple as listening to someone’s story. Our congregations should take the time to get to know one another and build deeper relationships, this puts us in a better place to recognize and respond when not only our hearts but our eyes are wide open.

Some people may be concerned about starting a relationship with a woman or child they suspect is being trafficked. They don’t want to make that person’s situation worse. What is your advice for getting to know a person who may be a victim of trafficking? What sorts of things are okay to do, and what kinds of things should be avoided?

We use the following tool in our training to help people gain a trafficking victim’s perspective.

- Think about things from our point of view. Never say you “understand” because you haven’t been there. Even so, try to put yourself in our shoes.

- Language counts. The words you use make a difference. Calling us “prostitutes” hurts us.

- Kindness and empathy go a long way. Even if we appear high, angry, homeless or dressed a certain way—don’t make assumptions. Showing us you care lets us know we can come to you for help.

- We might/will probably mess up again. There are lots of things that push us back into the life. Give us many chances. At some point, we will hit rock bottom, and we will need your help.

- We are good at reading people. We have to be. So we can tell if you really want to help us because you care or if you’re just saying you want to help us so we can help your case.

- We know things. Sometimes we might want to tell you. A lot of times, we won’t—at least not right away.

- We know more than you do about this life.

- We don’t want to be out there doing what we’re doing. You have to understand that. We’re just doing this for survival. We’re homeless, or we just need some way to keep going.

- We may act “hard,” but we have to have that “wall” up for survival. Deep down, we know we need help.

- Most of us didn’t get rescued as little girls. That doesn’t mean we don’t need your help now as adults.

- We have experienced more fear than you can imagine. Putting your pimp away doesn’t always get rid of that fear.

- We are good mothers. Give us multiple chances, give us the tools, give us time to get our lives together. Sometimes, the only thing worth fighting for is our kids—they’re the reason we get out. When you take away our kids, you take away our reason to fight.

- Listen to us. You may be “educated” and “professionals,” but even with your good intentions, you don’t know how things work in reality.

- Don’t just ask us for our “stories”—we are not on display! You need our input and feedback; so give us ways to be involved and have a voice before you start passing laws.

How can individuals and churches help Belle & Sparrow accomplish its mission of advocating for and empowering marginalized women?

Individuals and churches can help by recognizing that there is a need and then educating yourselves. Go with us to serve. Help us with funding our programs. Share our organization with your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues and others.

We would love to speak to your church, women’s organization, small groups, Bible studies, MOPS, etc.

Attend our upcoming (un)GALA on Sept. 21, and hear more about the work we are doing locally and globally. The event will be at the Art Centre of Plano, and tickets can be purchased here.

What future plans does Belle & Sparrows have?

Belle & Sparrows is in the beginning stages of opening a place for women not only to live and learn how to become self-sustaining but also giving them a skill or trade while paying them decent wages to take care of their family.

We realized we need to implement a multi-phase initiative in the local area to help bridge another gap in serving marginalized women, which is a social enterprise program to include housing, manufacturing and retail space in the future.

The Stella Projects will be a comprehensive, holistic model across several modalities with the first phase being the development and implementation of a consumable line of products.

We believe this project will introduce our services to an extremely underserved population of women. As a result, we anticipate a rise in awareness of the need in our own backyard, as well as becoming a beacon of hope to women in other situations around the U.S.

We want to change a culture that still allows human beings to be bought and sold. The Stella Projects, after all phases are complete, will meet a universal call for healing that echoes under bridges, in jail cells and on the streets of our communities.

Survivors of trafficking, prostitution, abuse and addiction share a story that has been universal since the beginning of time. It takes communities to place individuals in these situations, and it takes community to provide healing and empowerment to survivors. We are this community.

To learn more about Belle & Sparrows, you can attend their un(GALA) on Sept. 21 or visit their website.

How does sex trafficking tie into addiction, domestic violence, and incarceration?

How does sex trafficking tie into addiction, domestic violence, and incarceration?