American churchgoers say they’ll return post-COVID

NASHVILLE, Tenn.—Churchgoers aren’t attending in-person worship services yet at pre-pandemic levels, but most say they value gathering with their congregation and are eager to do so when the threat of COVID-19 ends.

A Lifeway Research study of 1,000 Protestant churchgoers in the United States revealed when COVID-19 no longer is an active threat to people’s health, 91 percent plan to attend in-person worship services at least as often as they did before the coronavirus pandemic. That includes almost a quarter (23 percent) who plan to attend more than they did previously.

Few regular churchgoers say they will attend less than before (6 percent), rarely attend (2 percent) or stop attending in-person services completely (1 percent).

Almost all churchgoers (94 percent) say they greatly value the times they can attend worship services in person with others from their church. Few (4 percent) disagree.

“Two-thirds of pastors whose churches were open for in-person worship in January saw attendance of less than 70 percent of their January 2020 attendance,” said Scott McConnell, executive director of Lifeway Research. “Many of these pastors are wondering if those who haven’t returned ever will. Nine in 10 churchgoers plan to when it is safe to do so.”

Young adult churchgoers, ages 18 to 29, are the most likely to say they will attend church more often after COVID-19 than they did before (43 percent).

Evangelicals by belief are more likely than those without evangelical beliefs to say they will attend more after the pandemic (28 percent to 19 percent).

Church involvement

About 9 in 10 churchgoers (87 percent) stuck with the same church throughout the pandemic. Few say they switched to another church in the same area (5 percent), switched churches because of a move (3 percent), or no longer have a church they consider their own (5 percent).

Among this group of Protestant churchgoers who attended at least once a month in 2019 and who still have a church, 56 percent say they attended worship services four times or more in January 2020 prior to the spread of COVID-19. Another 30 percent attended two or three times, while 7 percent say they attended once.

In January 2021, however, 51 percent didn’t attend any in-person services—22 percent said it was because none were offered by their church, and 30 percent chose not to attend their church’s in-person services. Around 1 in 5 (21 percent) say they attended in person four times or more. Slightly fewer (18 percent) attended two to three times and 7 percent attended once.

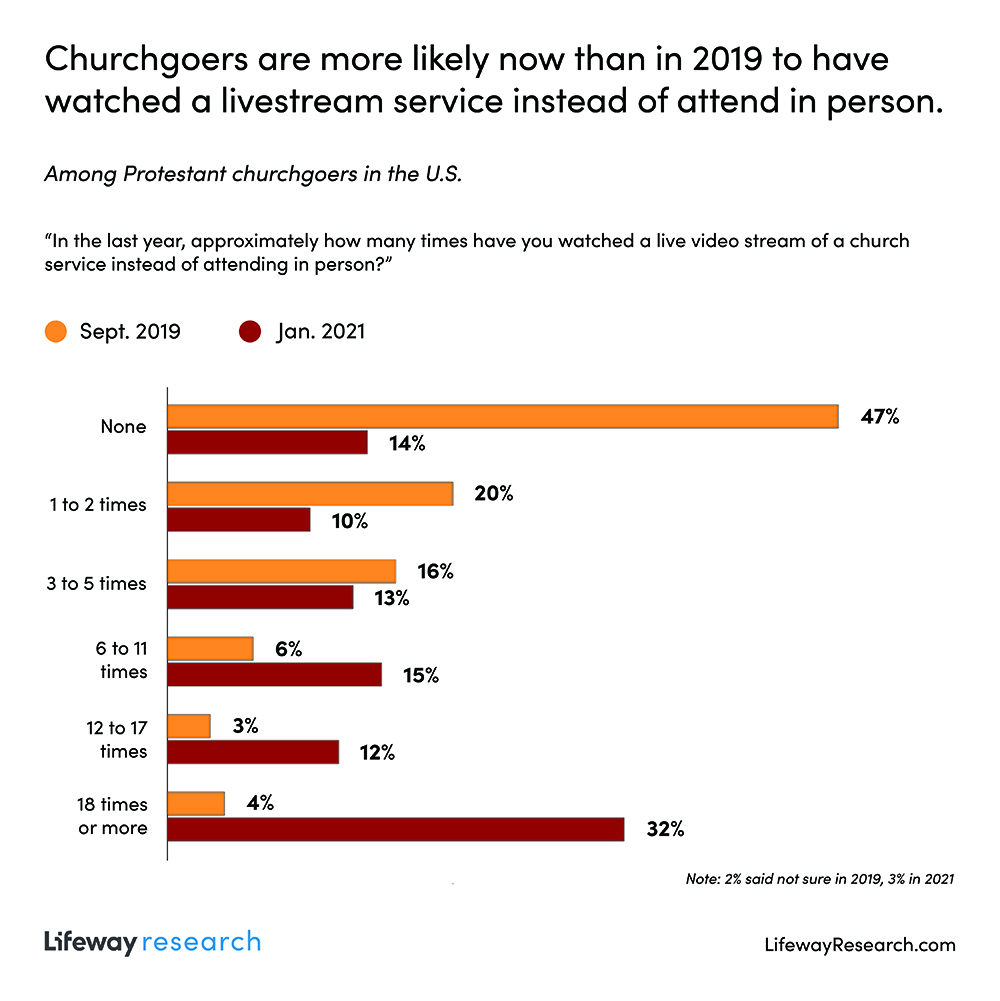

More than 4 in 5 churchgoers (83 percent) say they watched a livestream of a church service instead of attending in person at least once in 2020. Far more watched via livestream last year than said the same when asked before the pandemic.

A September 2018 Lifeway Research study showed 4 percent of churchgoers said they had watched a live video stream of a church service instead of attending in person 18 times or more in the last year, compared to 32 percent now. Two years ago, almost half of churchgoers (47 percent) said they hadn’t replaced an in-person service with a livestreamed one, while only 14 percent say the same today.

“Churches livestreaming services during COVID-19 has made this experience commonplace among churchgoers,” McConnell said. “Despite the increased exposure to this concept, however, relatively few have made this a weekly habit.”

Among churchgoers surveyed, 7 in 10 (71 percent) consider themselves to be a “devout Christian with a strong faith.” Around a quarter (23 percent) say they consider themselves a Christian, but not particularly devout. Fewer say they are a Christian but are not currently practicing the faith (5 percent).

Most churchgoers (54 percent) say the events of 2020 caused them to grow closer to God, including 27 percent who say they became much closer. Another 39 percent say they stayed about the same. Far fewer (7 percent) say they grew more distant.

Currently, 11 percent of churchgoers say they are questioning their faith, while 87 percent disagree.

“The faith of most churchgoers remains resilient despite a year filled with much uncertainty and fewer options for meeting in person with others from church,” McConnell said. “During these trying times, churchgoers were almost eight times more likely to relate to God more than less.”

Younger churchgoers (18 to 29) are the most likely to say they became much closer to God (37 percent), but also the most likely to say they are currently questioning their Christian faith (24 percent).

Personal impact

Thinking back on January 2021, few churchgoers say they lived life close to normal. Around 1 in 10 (9 percent) say they had a normal number of contacts with few precautions. Slightly more say they had a normal number of contacts with people outside their home but with precautions (13 percent). Another 1 in 10 (10 percent) say they had limited contact with others but took few precautions.

A plurality of churchgoers (36 percent) say they had a limited number of contacts with precautions (36 percent). Around a quarter (26 percent) say they only had very brief contacts such as essential shopping. For 7 percent of churchgoers, they had no contact with anyone in January.

For most churchgoers, the yearlong pandemic has brought some tangible challenges, including 8 percent who say they have been diagnosed with COVID-19.

More than 2 in 5 (42 percent) say someone in their church has been diagnosed with the disease and 18 percent say a fellow church member died from it. A previous Lifeway Research study, found 88 percent of Protestant pastors say a church attendee has been diagnosed with COVID-19 and 29 percent say a member died from COVID-19.

Around 1 in 7 churchgoers (15 percent) say they have lost income because of reduced hours at work, while 6 percent say they lost their job.

On a more positive note, many churchgoers have helped each other and reached out beyond their church. Around 2 in 5 (41 percent) say they have checked on others in their church, while a similar number 38 percent say people in their church have checked on them. One in 10 say others in their church have helped them with tangible needs. For 15 percent, the pandemic period has provided an opportunity to share the gospel with someone.

“Like other Americans, churchgoers have seen the effects of COVID-19 first-hand,” McConnell said. “Many churchgoers have also felt the benefits of being part of a church as members checked on them or provided assistance.”

The online survey of 1,000 American Protestant churchgoers was conducted Feb. 5-18 using a national, pre-recruited panel. Respondents were screened to include those who identified as Protestant/non-denominational and attended religious services at least once a month in 2019. Researchers used quotas and slight weights to balance gender, age, region, ethnicity and education to reflect the population more accurately. The completed sample is 1,000 surveys, providing 95 percent confidence the sampling error from the panel does not exceed plus or minus 3.2 percent. Margins of error are higher in sub-groups.

A

A

Pastors estimate more than a third of groups (36 percent) are meeting in person, while 25 percent are meeting online or by phone. Another third of church classes are not currently meeting, and 6 percent of classes no longer exist.

Pastors estimate more than a third of groups (36 percent) are meeting in person, while 25 percent are meeting online or by phone. Another third of church classes are not currently meeting, and 6 percent of classes no longer exist.

Pew describes its new 176-page

Pew describes its new 176-page

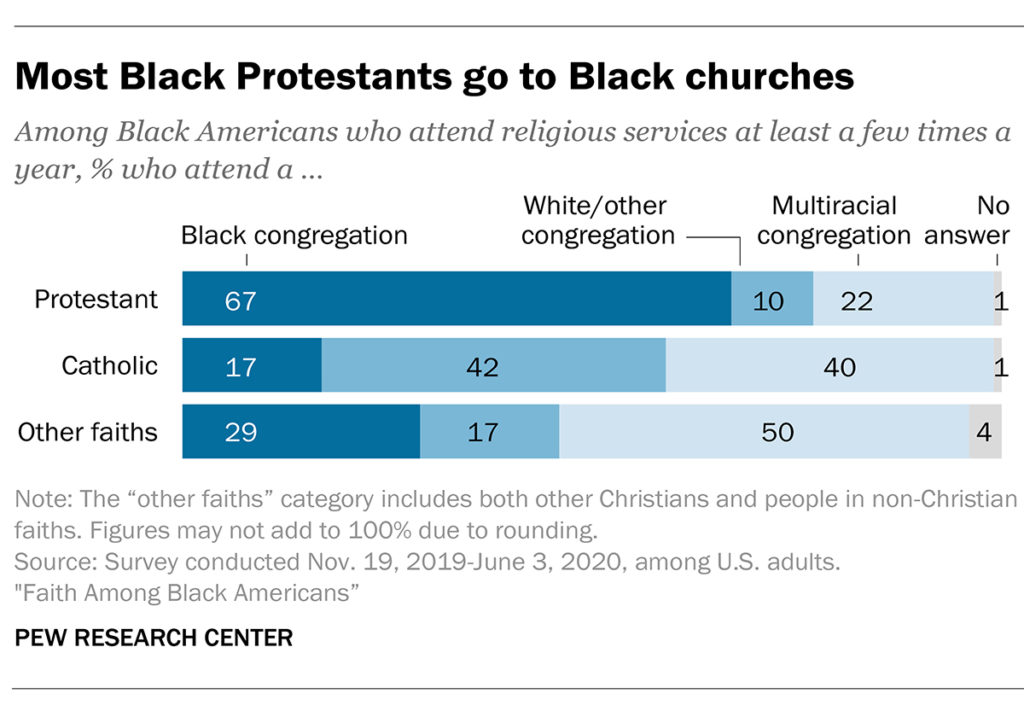

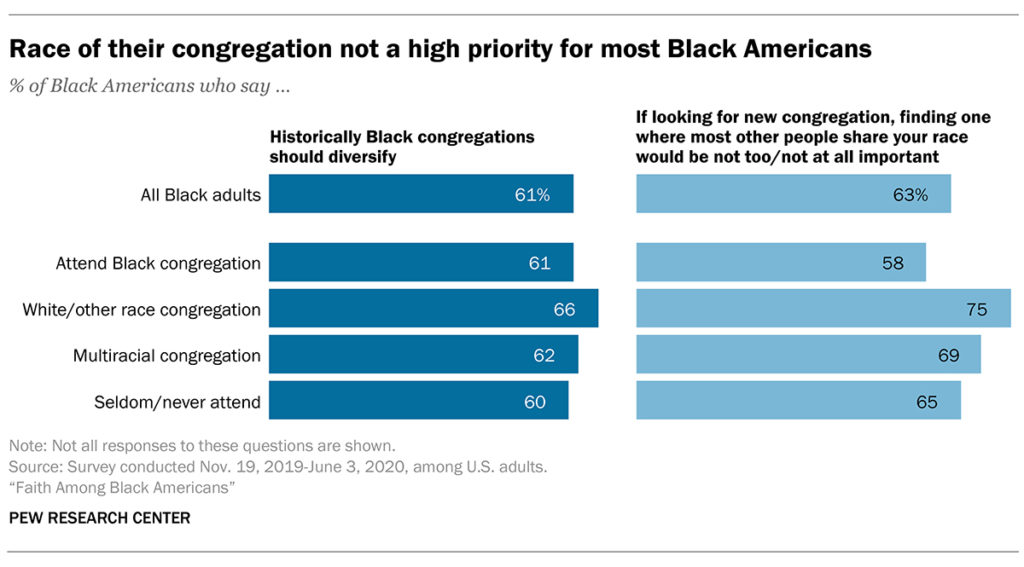

Those who attend white, multiracial, Catholic and other Christian churches almost uniformly were less likely to report these experiences. But more than half (54 percent) of Black Americans attending multiracial Protestant churches also reported that speaking and praying in tongues occurred in those settings.

Those who attend white, multiracial, Catholic and other Christian churches almost uniformly were less likely to report these experiences. But more than half (54 percent) of Black Americans attending multiracial Protestant churches also reported that speaking and praying in tongues occurred in those settings.

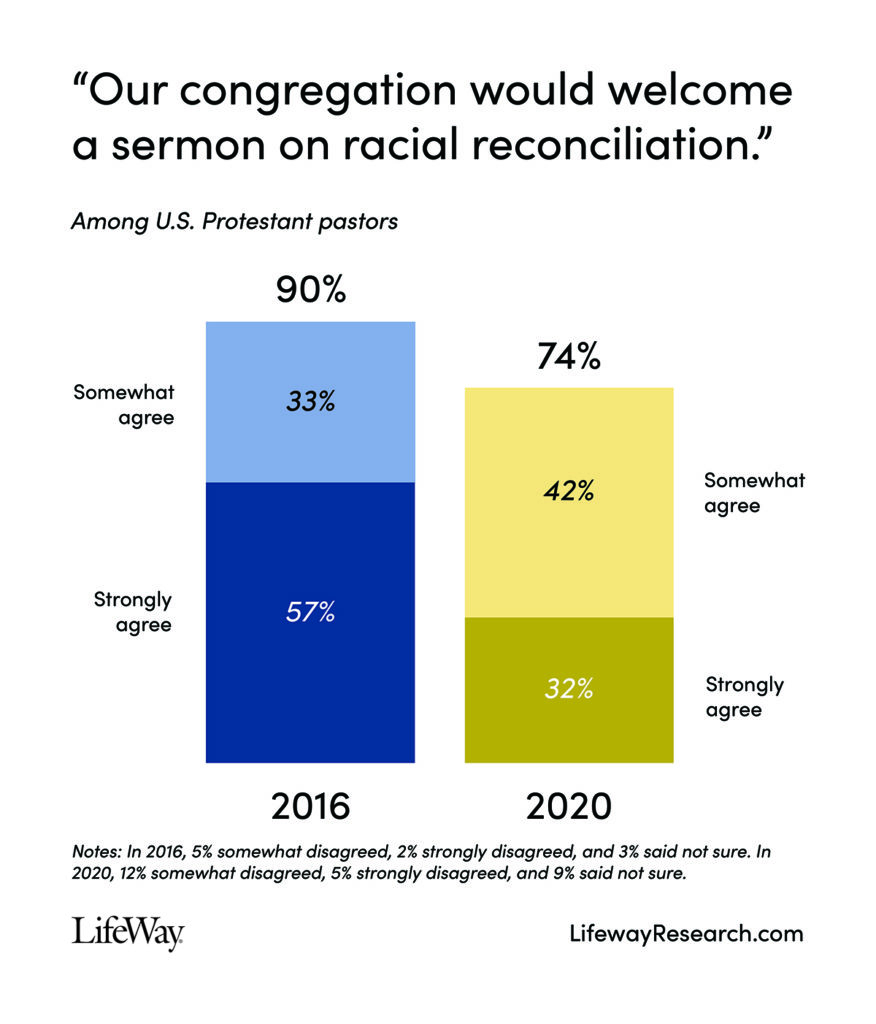

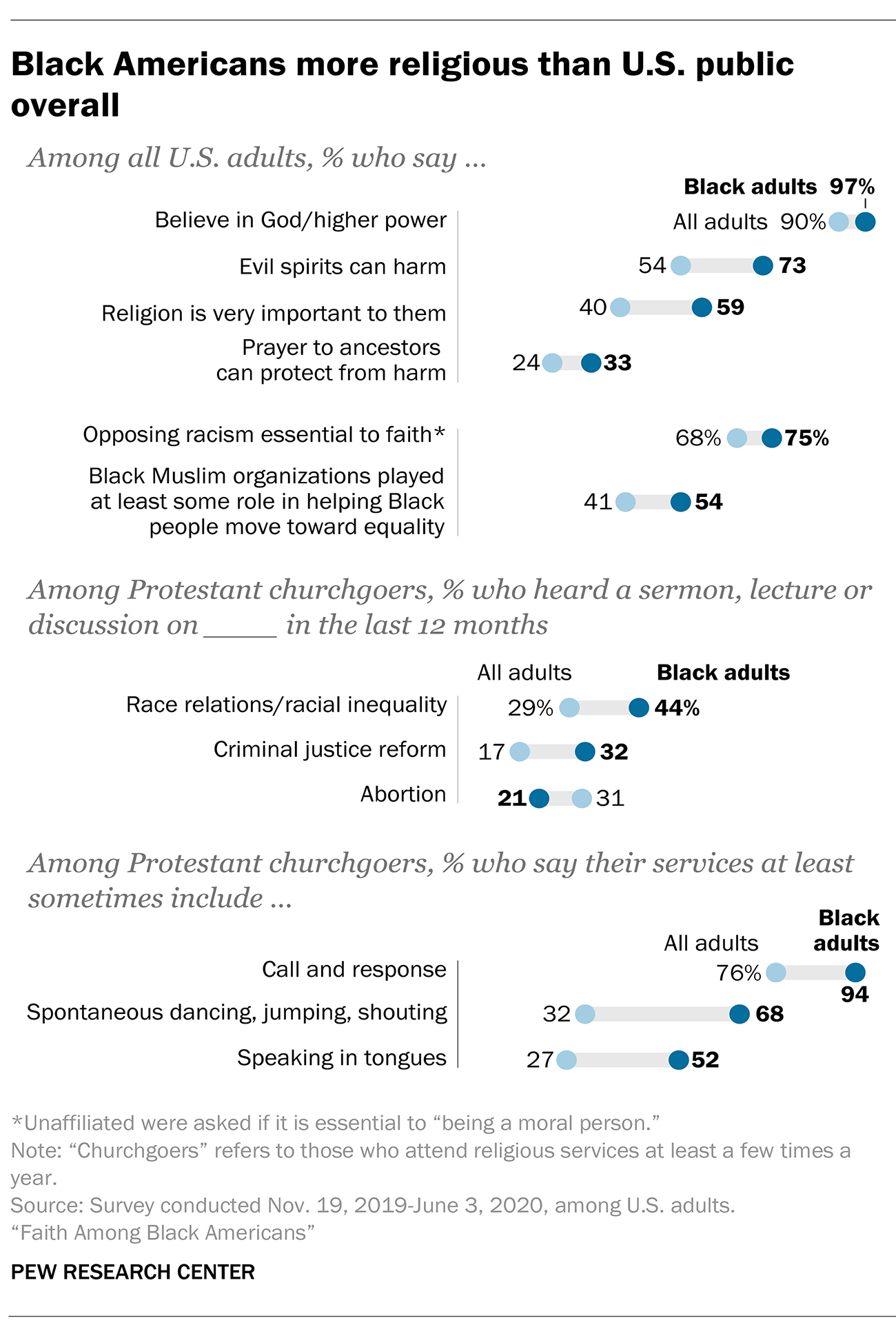

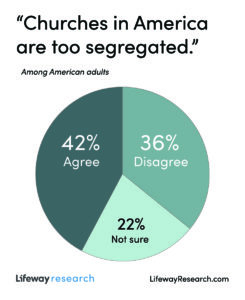

According to the most recent study, 46 percent say Americans have made worthwhile progress in race relations—28 points fewer than in 2014 when 74 percent said the same.

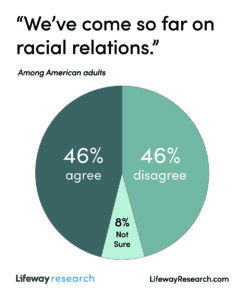

According to the most recent study, 46 percent say Americans have made worthwhile progress in race relations—28 points fewer than in 2014 when 74 percent said the same. Americans are divided over whether U.S. churches are too segregated. More than 2 in 5 (42 percent) believe that to be true, while 36 percent disagree and 22 percent aren’t sure.

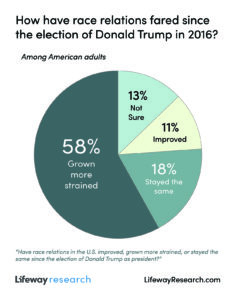

Americans are divided over whether U.S. churches are too segregated. More than 2 in 5 (42 percent) believe that to be true, while 36 percent disagree and 22 percent aren’t sure. African Americans (72 percent) are most likely to say race relations grew more strained under President Trump, but majorities of Hispanics (61 percent) and whites (54 percent) also agree.

African Americans (72 percent) are most likely to say race relations grew more strained under President Trump, but majorities of Hispanics (61 percent) and whites (54 percent) also agree.