Our men’s ministry group from First Baptist Church in West took a road trip to Hico, where we found the “Mini-Tank Battlefield.” Each of us got our own personal “mini-tank.” It functioned much like a real tank, except it had room for only one person and its only arsenal was a paintball gun.

Excited about spending the day with my friends and thoroughly enjoying such a unique experience, I drove my mini-tank down a little trail through the woods. As I entered a clearing, I immediately encountered a relentless barrage of paint pellets. They quickly transformed my green tank into a multicolored vehicle of shame and its driver into a bruised and battered defeated warrior.

Every seasoned leader has had a similar experience. Most leaders have been through the surprise attack scenario more than once. Ministers and church lay-leaders are not exempt. Unexpected confrontations can happen in the hallways of a church just as easily as they can on a mini-tank paintball course.

When someone confronts a leader with criticism or accusations, the attacker has the advantage of surprise. Before addressing the leader, he has had the opportunity to plan his course of action, choose his words, and perhaps even recruit his allies.

The leader, however, is not given the opportunity to prepare, but most likely will be held accountable for his or her response. To avoid making things worse with our own emotional reactions, leaders need a rational way to process a perceived attack and determine how to respond.

One approach that has proven helpful is to ask two questions. First, the leader should not settle for anything less than an honest answer to the hard question, “Is the other person right?” When we feel like we are under attack, our defenses go up and we reject anything that seems like it might cause pain. When we are in that mode, however, we might miss out on a valuable opportunity for personal growth.

Maybe there is some validity to the observations being expressed by the other person. Perhaps they can help us see something about ourselves or our organization that we might have missed without the benefit of their perspective.

It is also quite possible, however, that what they are saying is not right. We must not automatically assume that because they are upset, they must be right. We need to wrestle with the question and be willing to determine the answer to the best of our ability.

The second question should be considered independently of the first. Setting aside our evaluation of the validity of the words, we need to consider the manner in which the words were spoken or written. We must ask, “Is the person being reasonable?” Regardless of how we answered the first question, we now must look at how they are treating us and whether their behavior is reasonable. If they are remaining calm, staying focused and being fair in their choice of words, our response should be different than it will be if they are being hurtful, unfair or overly dramatic.

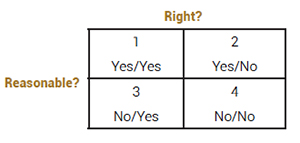

“Is the person right?” “Is the person being reasonable?” The key to a rational response is identifying how our answers to the two questions work together. The two questions help us separate and process very different issues. Once we have settled those issues adequately, we can see how they relate to one another, and we can determine our response. Alliteration helps here: My rational response is based on whether the person is right and reasonable.

I normally visualize this process in a grid. I am learning to picture the grid when I feel attacked or find myself in an unexpected confrontation. The grid has four quadrants that represent the possible answers to the two questions.

- If the person is right and she is being reasonable, I need to give that person my full attention. We may set up a time to discuss her concerns later so I can adequately consider them, but I should let the person know she is being heard.

- If the person is right, but he is not being reasonable about it, I am faced with a personal challenge. I should weigh seriously the content of the message without allowing the person to hurt my feelings or control me with his misbehavior.

- If the person is not right, but she is being reasonable, I need to listen attentively and respond patiently in hopes that I can help clarify her misunderstanding.

- If the person is not right and he is not being reasonable, I need to protect myself, and more importantly, I need to protect the church or organization that I lead. I cannot do that by being bullied, nor can I do that by giving in to the temptation to join him in his misbehavior. I need to de-escalate the situation and walk away from it. Later, with wise counsel, I can determine next steps if there need to be any.

This is too much to think about in the heat of the moment. That is precisely why we need to make sure the grid is stored in our memory bank, and we have learned the process before we need it. The more we think about it beforehandand the more we practice it, the more natural it will become. Soon, we will not even have to see the grid in our mind’s eye anymore, because we automatically will process the two questions and determine an appropriately rational response.

Remember: “A soft answer turns away wrath, but a harsh word stirs up anger” (Proverbs 15:1).

John Crowder is pastor of First Baptist Church in West, where he has served 27 years. This article first appeared in CommonCall magazine.

We seek to connect God’s story and God’s people around the world. To learn more about God’s story, click here.

Send comments and feedback to Eric Black, our editor. For comments to be published, please specify “letter to the editor.” Maximum length for publication is 300 words.