Editorial: The flaws in “religious liberty” laws

“Freedom” may be the most contentious word in the American conversation. At least, it’s the most paradoxical.

Marv KnoxAs the social/moral divide in our nation widens, strain on the definition of “freedom” escalates. What does it mean when “freedom” becomes the banner of groups with opposing viewpoints?

Marv KnoxAs the social/moral divide in our nation widens, strain on the definition of “freedom” escalates. What does it mean when “freedom” becomes the banner of groups with opposing viewpoints?

For example, are employees free to receive contraceptives as part of their health-care benefits, or are their employers free to deny those benefits, based on religious beliefs? And now that homosexual couples are free to marry, should vendors whose religious beliefs oppose homosexual behavior be free to deny their services for same-sex weddings?

Hard to have it both ways.

Increasing tension on the meaning of freedom has led to legislation, particularly at the state level. The most interesting situation recently occurred in red-state Georgia, where the Republican governor, Nathan Deal, and the Republican-dominated legislature locked horns. The lawmakers passed a “religious liberty” bill that would legalize discrimination against homosexuals, based on religious beliefs. Deal vetoed the bill, based at least in part on his religious beliefs. (At this writing, legislators were threatening a special session to override the veto.)

Bi-directional flak

Deal caught flak from both directions. Liberals accused him of only taking his stand because of pressure from big businesses, which threatened to pull out of Georgia. Conservatives likewise criticized him for cratering, as well as being a liberal. Only Deal knows the extent to which business influenced his decision. But if he is a liberal, then some of Baptists’ most revered forebears were liberals, too.

Deal, a member of First Baptist Church in Gainesville, Ga., and a graduate of Mercer University, a Baptist school, referenced his required Old Testament and New Testament classes at Mercer when he first threatened a veto: “I’m a Baptist, and I’m going to get into a little biblical philosophy …,” he said. “I think what the New Testament teaches us is that Jesus reached out to those who were considered the outcasts—the ones who did not conform to the religious society’s view of the world—and said to those of belief, ‘This is what I want you to do.’”

He illustrated by noting Jesus showed compassion on the woman at the well, a moral and religious outcast. “I think what that says is that (Jesus) says that we have a belief in forgiveness and that we do not have to discriminate unduly against anyone on the basis of our own religious beliefs.” While “it is important that we protect religious beliefs,” Deal, who described himself and his wife as “traditional marriage people,” added, “but we don’t have to discriminate against other people to do that.”

Keeping good comany

Denunciations from his fellow Baptists to the contrary, Deal stands in line with Baptist pioneers Thomas Helwys (17th century England), Roger Williams (17th century America), John Leland (18th century United States) and George Truett (20th century Texas), who championed religious liberty—not only for Baptists and other Christians, but for all people. They guided their contemporaries to seek solutions to religious challenges that respected the beliefs—and dignity—of all people.

As the prevailing culture turns further away from their beliefs and comfort zones, some Baptists and other conservative Christians are tempted to exert the last vestiges of their middle-class majoritarian power to pass “religious liberty” laws that protect their privilege.

Wrong, quadrupled

This would be wrong on four levels:

• It violates the example of Jesus, who loved others and commanded his followers to do likewise.

• It denies Baptist heritage, which looks out for the underdog and seeks the welfare of all people.

• It’s lousy evangelism, since exclusion pushes unbelievers from Jesus.

• And ultimately, it’s destructive, because power reserved for the majority won’t help Christians when they become a minority.

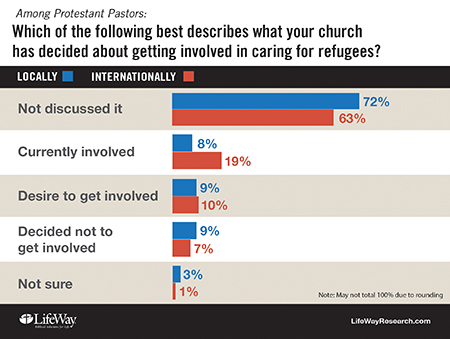

Churches, not so much

Churches, not so much