Parolee’s baptism tells of redemption outside prison walls

Anansi Flaherty, a backup fullback on Katy High School’s 2000 State Championship team, gave his life to Christ in prison. On Dec. 19, 2024, he was baptized—“raised to walk in new life”—outside those walls.

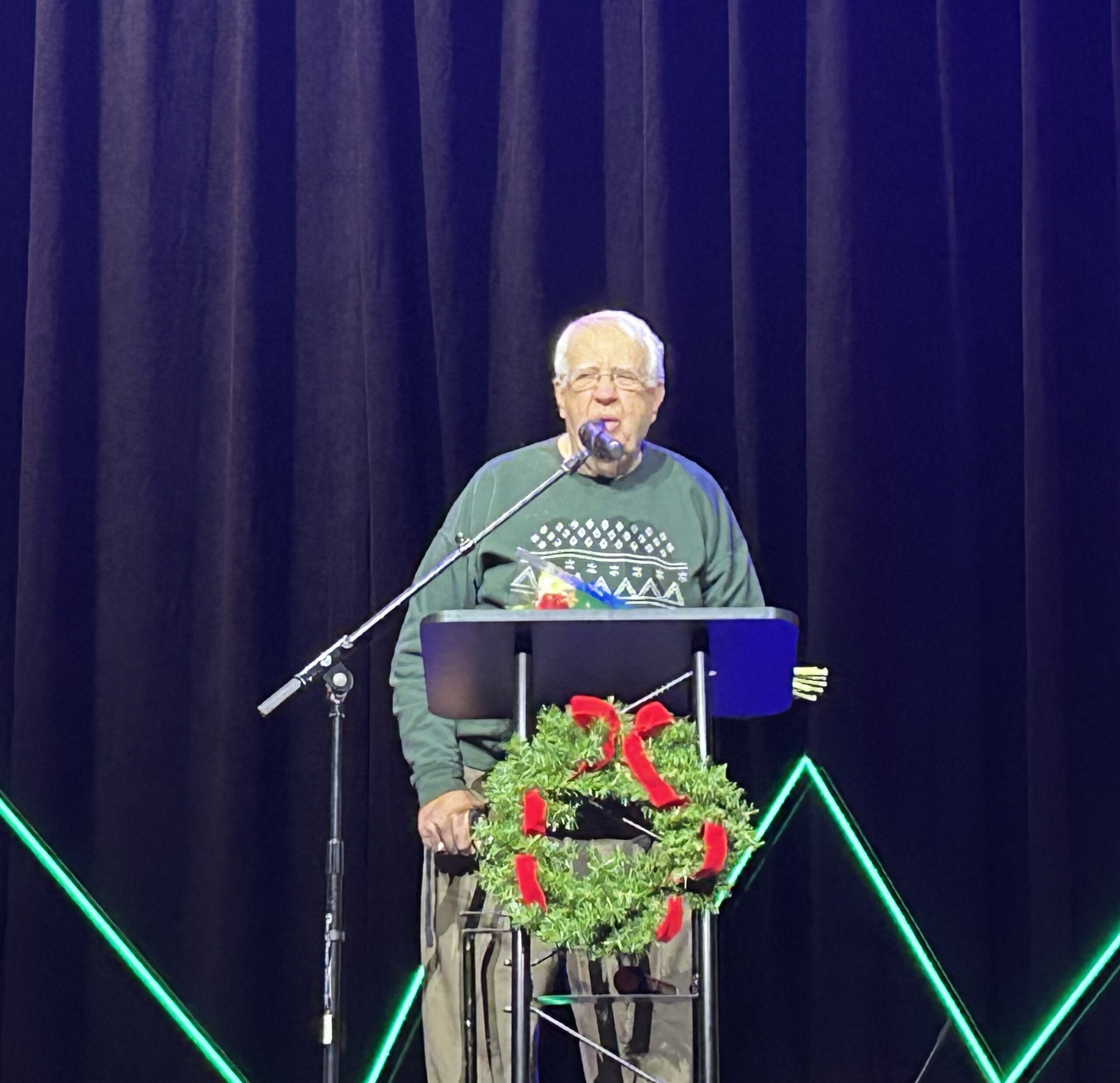

In the presence of the First Baptist Church in Burleson’s Primetimers senior adult ministry and Don Newbury, retired HPU president and retiring co-director of senior adults at the church, Flaherty participated in the luncheon program—featuring his faithful coach and him. Then he climbed into a metal trough to make his faith commitment clear.

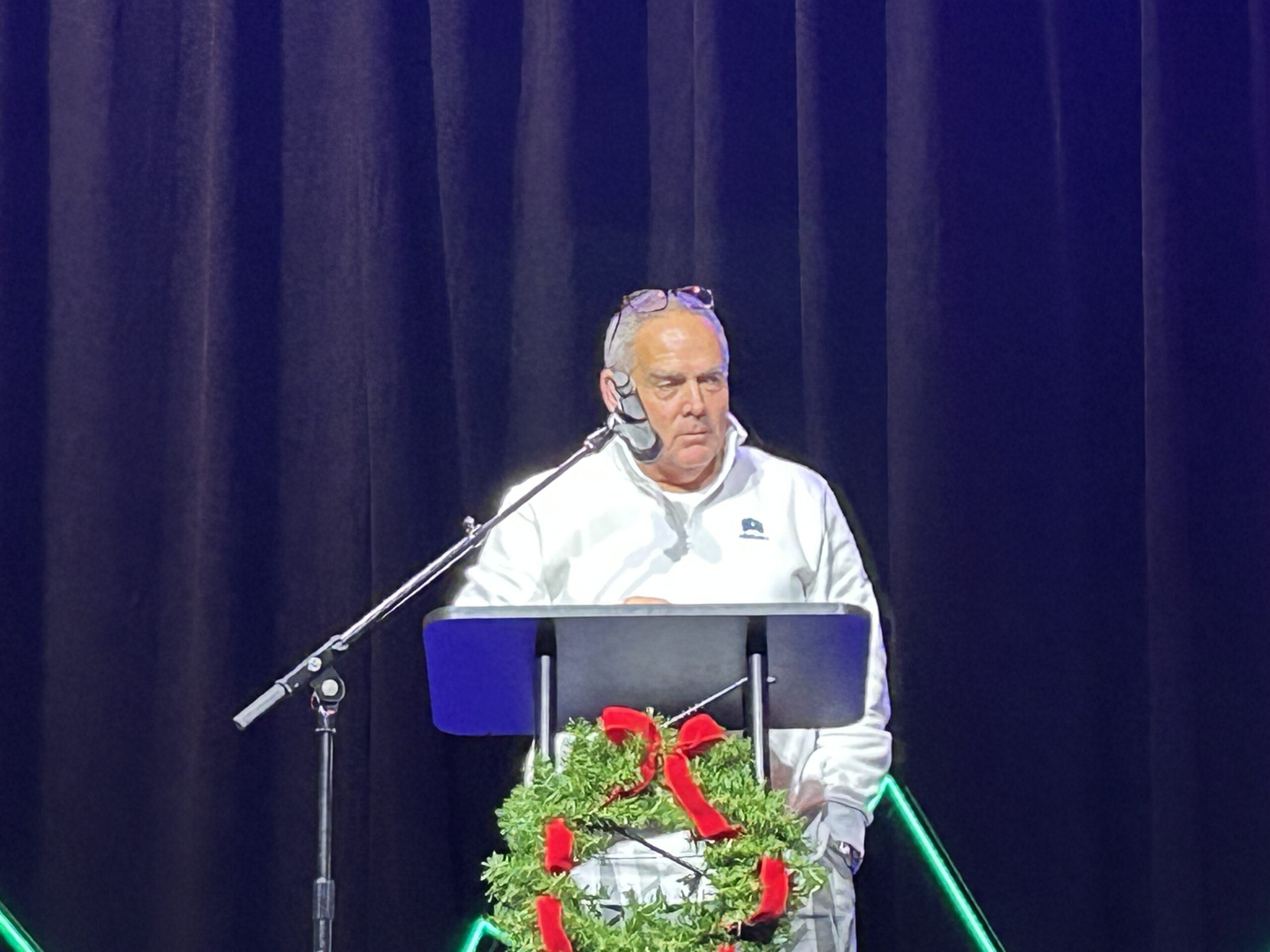

Flaherty’s high school coach, Jeff Dixon—who has provided support and familial care since first seeing reports of the terrible crime that led to Flaherty’s incarceration—knelt beside the trough. Jack Crane, pastor of Truevine Missionary Baptist Church in Fort Worth, dipped Flaherty beneath the water.

“God is at work here,” Dixon noted at multiple points in his presentation leading up to the celebrated redemption symbol. Those who could stood and clapped after the baptism.

Many in the room, Newbury noted, had followed Flaherty and Dixon’s story along with him, praying and supporting the young man whose life had taken such a tragic turn, now bearing witness to his redemption this Christmas season.

It was in the Christmas season of 2002 when the Fort Bend County sheriff’s department received a call about a “suspicious male walking down the street.” A witness described large amounts of blood on this clothing and body, a 2003 article reported.

That day was not discussed in the Primetimers’ luncheon program, apart from the handout, and little about it is publicly available or clear. According to several reports, Flaherty remembers few details of that day.

Reports say he recalled being high on drugs, and when he was approached by officers, the 19-year-old said he had killed his mother.

In a plea deal, Flaherty was sentenced to 40 years for first-degree murder, eligible for parole in 2022.

The hero of the story

“God’s the hero of every story,” Dixon began his message to the Primetimers’ luncheon. “And he is most certainly the hero of this one.”

Dixon—whom Newbury described along with his wife Mandy as being among the most notable Howard Payne graduates—explained in his early coaching career, he was “in hot pursuit of me,” rather than attuned to God’s leading.

His early years as an assistant coach, under Bob Ledbetter at Southlake Carroll, led to assisting Coach Mike Johnston in his hometown of Katy. Then he moved to Ennis, where he and his family intended to stay.

In Ennis, the Dixon family lived within walking distance of the church, and, Dixon noted, he and Mandy became more serious about prayerfully listening to God.

When Johnston called him about returning to Katy to assist, which, Dixon explained, would have been seen as a coveted opportunity under a highly respected and successful coach, he initially turned Johnston down.

The family loved Ennis, and Dixon loved to teach. The position in Katy was for P.E. and assistant football coach, but Dixon taught math and didn’t want to give that up, he said.

Johnston understood but “asked me to remain in prayer over it,” so Dixon and his wife did.

Johnston called back just before the end of the year to explain a math teacher unexpectedly was leaving, so if Dixon came to Katy, he’d be able to coach and teach.

“We were convinced because of prayer that God called us to Katy,” Dixon said, noting when “you find yourself in God’s will, he turns you to where he wants you to be.”

They still cried when they pulled away from Ennis, the little town they’d loved so much, but “God was at work,” he said.

Back in Katy, Flaherty played a position Dixon coached, fullback. He recalled Flaherty being a kid everyone liked. Even during disciplinary-type drills designed to “get your attention,” Flaherty kept smiling when anyone else would have been miserable, Dixon said.

Dixon explained assistant coaches were held responsible for the eligibility of the players in their position. Flaherty struggled with math, so he spent many days in Dixon’s office for tutoring. At this time, Flaherty lived by himself in an apartment near the school.

His family would come to check on him often. But at 16 years old and recently released from juvenile detention, he was essentially on his own. Dixon noted if it wasn’t for football, Flaherty would have been in a lot of trouble, musing, “Can you imagine being by yourself like that?”

Sometimes coaches would buy him groceries. Weekly, the Dixon family hosted a meal for running backs at their home. The family got to know Flaherty and care about him, Dixon recalled.

When he graduated, Flaherty went to Texas A&M in Kingsville to continue playing football but came home for Christmas break in 2002. Dixon and his wife, on break themselves, turned on the news—where in the mugshot accompanying a tragic story, they saw a familiar face, Dixon said.

The impact of faithful friendship

Dixon went to see Flaherty in the Fort Bend County jail and continued to visit him weekly for a year. Dixon noted he was present in the courtroom when Flaherty was sentenced to 40 years.

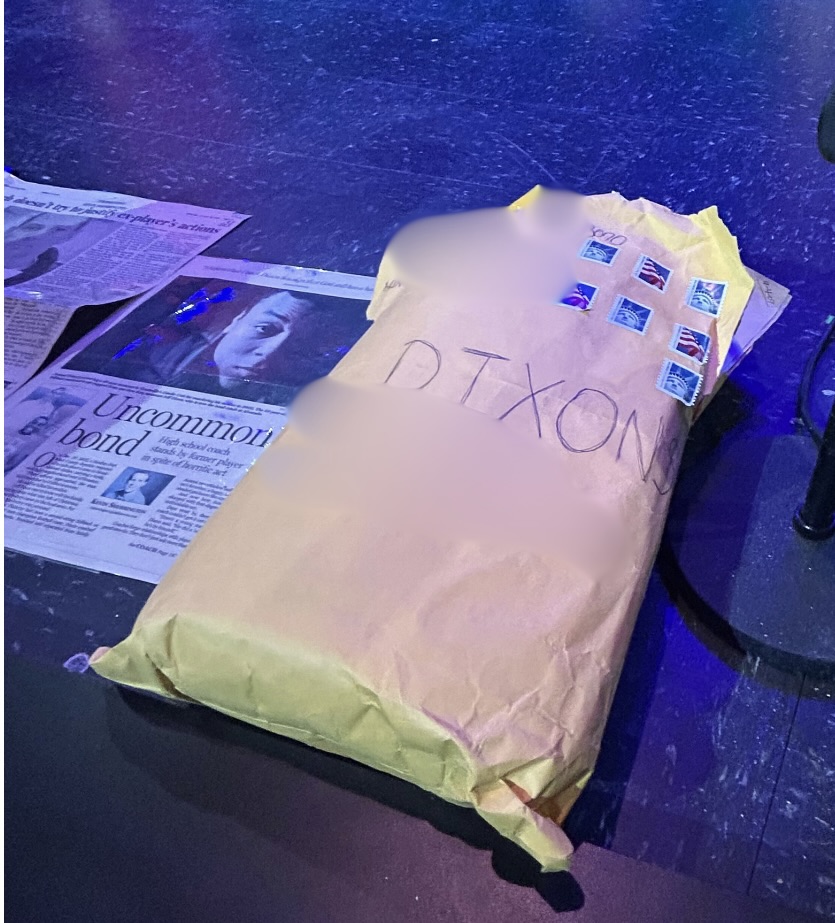

Then the Dixon family went to work praying for Flaherty. Flaherty refers to his time in the penitentiary as being “in the belly of the fish” in a reference to Jonah. All during Flaherty’s incarceration the two men exchanged letters.

Dixon often traveled to visit Flaherty, as he was moved around the state to various penitentiaries. For 22 years, the men stayed in touch, and Flaherty shared in his letters how God was working in his life, signing the letters with “In His grip” and “Your Second Son, Anansi.”

When Dixon asked Flaherty whose grip that was, his answer was, “Yahweh’s.”

For 22 years, Dixon said his conversations with Anansi were through thick glass by a phone with a bad connection.

When he got word in November of Flaherty’s parole and that he was being released to a halfway house in Houston, the family headed there, not realizing there still were restrictions that normally would prevent them from seeing him.

When they arrived, they were permitted to see him and hug him. God was at work there, too, Dixon said, because the parole officer happened to be there and explain Flaherty needed a plan for when his remaining 20 days in the halfway house concluded.

They made a plan, and Flaherty now lives in the Fort Worth area.

Crane, who baptized him, has been handling Flaherty’s transportation to weekly Bible studies at Truevine, until Dixon teaches him how to drive his first car, a standard transmission, gifted to him through a ministry that provides cars to parolees.

Dixon sees that story too as proof “God is at work here.”

In the question and answer with Dixon, Flaherty explained he began to understand the power of forgiveness as an adult in prison.

Flaherty noted in his youth he had anger issues, believing he had to fight back against “the man” and racial injustice. But he learned in prison if he could “let it slide” when a guard upset him, that guard might stick up for him when he needed it.

“You know when someone is really for you,” Flaherty said, when Dixon asked him about friendship. True friendship should be unconditional, not circumstantial, Flaherty asserted.

Just before the baptism Flaherty asked, “Can I leave with an acrostic? G-O-S-P-E-L—God’s Obedient Son Providing Eternal Life.”