Hunger and Poverty Summit plants seeds of hope

WACO—One might expect somberness to describe the overall tenor of a conference built around solving a global crisis of hunger and poverty, but this year’s summit orbited a theology of hope.

Jenny Howell, director of the theology, ecology and food justice degree program at Baylor University’s Truett Theological Seminary, said problems of hunger, poverty and land degradation have been described as “wicked problems” no single sector can solve.

But these problems can be tackled with collaboration.

Biological research has observed organisms in “webs of connection” show better propensity toward resiliency, she noted.

When hard times come, it’s time to come together and collaborate to solve these “wicked problems.” Perhaps now more than ever, this is a time for collaboration, Howell suggested.

Hope in Africa

These changes are necessary, Howell said, “for the good of my neighbors, for the love of God and the love of place.”

Keynote speaker Father Emmanuel Katongole, professor of theology and peace studies at Notre Dame University, told of his work with Bethany Land Institute in rural Uganda.

He said he never guessed land management, food insecurity and poverty in his home country would become his preoccupation as a theologian, but “the cry of the earth and the cry of the poor go together.” The cries of both in Uganda spurred him to action.

In a world facing serious problems of hunger, poverty and environmental degradation: “We need hope, and we need it badly,” he noted.

Katongole saw in his home country, Uganda, the “slow violence” of global warming, deforestation and economic uncertainty merging “to shape a continent steeped in contradictions and challenges,” and he wanted to try to channel his energy into constructive change.

He and his partners in ministry wanted to help young people facing existential questions learn to value a simple life in their communities, grow food and make money.

They created a campus dedicated to young people working together to address the “three Es” —education, economics and environment—while he worked on his book Born from Lament: The Theology and Politics of Hope in Africa.

In their work, he observed they were dealing with a social problem, an ecological problem and a spiritual problem.

“We have forgotten what it means to belong to the earth,” Katongole noted. And that is a crisis of belonging.

Not knowing “who we are” results in “internal deserts” that eventually “beget external deserts.”

His team decided to try an integrated approach to solving the crises through a spiritual lifestyle of caring for the land where students serve as “caretakers.”

“Something happens when we touch the ground,” Katongole noted.

Human lives are intended to be grounded with God, one another and the earth, he asserted. If one of those pieces is disrupted, the others suffer. That leads to a spiritual crisis of alienation.

But working the land together builds community and identity leading to a deep sense of “who we are as created by God.”

“The actual work of saving the world will always be humble,” he said. So, “start small, start well, and start now,” and learn to live in a place of hope, Katongole urged.

Hope in Fort Worth

Scripture records God’s “preferential option for the poor and vulnerable” and requires God’s people to have that same preference on behalf of the poor, said Heather Reynolds, managing director of the Lab for Economic Opportunities at the University of Notre Dame.

Reynolds, former president and CEO of Catholic Charities Fort Worth, described how she felt God asking her: “Heather, how are you preferring the poor right now—in this moment, in this space and in this place?”

In response to that question, she noted three bullet points scribbled in her personal devotional journal.

- Show up. She recalled weekly counseling sessions with Lois, a woman in her 80s who told such captivating stories, Reynolds felt less like a helping professional and more like she was enjoying “coffee with a girlfriend.” Reynolds said she thought Lois overpaid for the $10 sessions, because the therapist gained more from them than the client.

- Shine brightly with hopeful optimism. She cited the story of Stephen, the first Christian martyr, as recorded in the New Testament Book of Acts. As Stephen offered a prayer of forgiveness for those who stoned him, his face was “aglow” like an angel.

“I have to envision that glow from Stephen’s face came from a deep-seated wisdom that he knew what was coming next—a hopeful optimism about uniting with Christ,” Reynolds said.

Similarly, she said, her memories of people who had a deep impact on her life are surrounded by a “glow of hopeful optimism.”

- Activate truth. Don’t settle for good intentions. People in poverty “are worthy of our best efforts,” and that means practicing evidence-based approaches to tackling poverty that produce proven results, Reynolds said.

“Our hope is not in these times,” Reynolds said. “Our hope is not in a political candidate. Our hope is not in ourselves. Our hope is in a vision of what is to come. We are called to be hope-filled people.”

Hope is a verb

Norman Wirzba, professor and senior fellow of Christian theology at Duke University’s Kenan Institute of Ethics, offered the last keynote of the summit.

Wirzba asserted hope is one of those terms “people can’t do without,” but “do not assume that people want hope.”

Young people look at a future of “diminished possibilities,” due to climate change, which he said are the result of the actions of “old, white men” like himself.

“So, when young people hear people like me say: ‘Hey, be hopeful. Don’t give up,’ they say: ‘Are you kidding me?’ You’re on your way out. We’re not, and we have to live with what you are leaving us.’”

Many young people who face serious depression or other mental health issues can’t imagine having children in this world. This is not a small matter, he said.

“But we have to be honest about hope. And we have not been honest about our language around hope,” Wirzba said.

Religious sayings intended to be hopeful, like: “Don’t worry. God’s got this,” create the “ultimate bystander effect,” Wirzba said, noting that’s actually a very cynical way to think.

The techno version of hope—where humans retreat to underground bunkers, hope artificial intelligence will save the future or make plans to colonize Mars—are as cynical and empty as the religious version.

Both versions evade “our responsibility that gets repeated over, and over, and over again throughout Scripture, which is the responsibility to be in covenant relationship with God, other people and with our land,” he asserted.

These versions of hope are “supremely dangerous,” irresponsible and part of the reason young people are saying: “Stop talking about hope.”

Hope is not optimism, Wirzba noted. “It’s so, so hard to see what is happening” in the world today, and he is not much more optimistic than the young people, “who have resigned themselves to the fact that the future is going to suck.”

So, he suggested, give up on optimism that never challenges the status quo. Because optimism that things will work out when they are not working out leads to despair, hope is better than optimism.

“Hope is a movement against despair.” But, it’s not something you have or possess.

“Hope is something that involves you in the world in a new way,” Wirzba explained. It’s a verb, “something you do.”

Hope is figuring out how to nurture, protect and celebrate what you love, he explained. Hope is activated by answering the question, “Who or what do you love?”

And when we give our love, kindness and attention to our world, it responds.

“Hope is love in the future tense.” It gets individuals off the couch to ask: “What does love require of me?”

Then hope spurs decisions with the future of what is loved in mind. Communicate that the world is “love-worthy,” Wirzba urged—be agents of hope, and make it more delicious here.

With additional reporting by Managing Editor Ken Camp.

The brief video shows the interior of a storefront office where five individuals—two of whom appear to be minors—worked at computer terminals to print out lottery tickets. The Baptist Standard possesses the unedited video but is not posting it since it depicts minors.

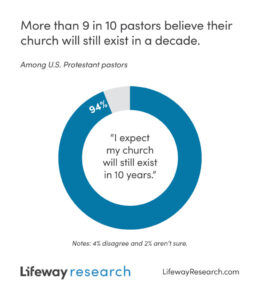

The brief video shows the interior of a storefront office where five individuals—two of whom appear to be minors—worked at computer terminals to print out lottery tickets. The Baptist Standard possesses the unedited video but is not posting it since it depicts minors. A new survey from Nashville-based Lifeway Research found 94 percent of Protestant pastors believe their church will still be open in 10 years, with 78 percent strongly agreeing that will be true.

A new survey from Nashville-based Lifeway Research found 94 percent of Protestant pastors believe their church will still be open in 10 years, with 78 percent strongly agreeing that will be true.