Rapture triggers haunt the Left Behind generation

WASHINGTON (RNS)—When a pandemic caused shutdowns across the globe in March 2020, Stacie Grahn thought it was the literal end of the world.

“I thought: ‘This is it. We’re all in our homes. Is this when we’re all going to disappear?’” Grahn said in a phone call from British Columbia. “With the vaccine, I thought: ‘Is this how they’re going to separate us? Is this going to be the mark of the beast we have to take?’”

For those like Grahn who are taught the rapture can happen at any second, the End Times are more than fodder for apocalyptic fiction. Fear-saturated stories about the saved being transported to heaven while the world faces havoc and hellfire can generate lifelong panic, paranoia and anxiety, reorienting people’s lives around what’s to come instead of what is.

These religious beliefs have societal implications, too. Why care about the refugee crisis or climate change if the world is doomed?

Rapture a relatively recent concept

Belief in the Second Coming of Christ is as old as the church, but the concept of the rapture is a relatively recent early 19th-century phenomenon, most often embraced in evangelical or fundamentalist circles.

In the late 20th century, it was reinforced through popular media, including Hal Lindsay’s 1970 bestseller The Late Great Planet Earth, which interpreted world events as signs of the end times, as well as the 1972 thriller A Thief in the Night and, in the 1990s, Tim LaHaye and Jerry B. Jenkins’ wildly popular Left Behind series.

In the late 20th century, it was reinforced through popular media, including Hal Lindsay’s 1970 bestseller The Late Great Planet Earth, which interpreted world events as signs of the end times, as well as the 1972 thriller A Thief in the Night and, in the 1990s, Tim LaHaye and Jerry B. Jenkins’ wildly popular Left Behind series.

But, as Grahn could tell you, these ideas aren’t relics of the past. Grahn’s grandmother first introduced her to the rapture at a young age via videos of End Times ministries and preachers like JD Farag. Anything her grandmother planned was with an asterisk.

“We can plan that, but the Lord could be coming back,” Grahn recalled her grandmother saying.

Prepping for disaster

Unlike Grahn, Nikki G, 46, came to view the rapture as gospel later in life. In 2010, she uprooted her life to join the International House of Prayer in Kansas City, Mo. As a survivor of several high-control religious groups. she asked to go by her first name due to safety concerns.

Nikki was attracted by the fervency of the group, which has been hosting 24/7 worship and prayer since 1999 and has a distinct End Times flavor.

“We believe that the church will go through the Great Tribulation with great power and victory and will only be raptured at the end of the Great Tribulation. No one can know with certainty the timing of the Lord’s return,” the organization’s website says.

As a result of the apocalyptic messaging she heard in these groups, Nikki said she rejected materialism, began canning food and strategized survival tactics. But prepping to survive until the rapture took a toll on Nikki.

“It’s very dehumanizing,” Nikki said. “You’re not present. You’re always in the future. You are disassociated from your body, your nervous system and yourself, and ultimately you become the theology. … I was no longer Nikki, when I was in all of that.”

She experienced nightmares, flashbacks and insomnia years after leaving.

Anecdotal evidence of anxiety and fear

Therapist Mark Gregory Karris said, while there’s little research on rapture-related trauma, anecdotal evidence suggests people can experience anxiety, fear and disrupted life plans because of such teachings. He said it especially is true among those who emphasize the immediacy of the rapture, the torment of those left behind and the need to be good enough to win God’s approval. Some who ingest these beliefs see future plans as futile, even faithless.

That was the case for Diana Frazier, 39, who grew up in an Assemblies of God church in Poulsbo, Wash.

“I remember sobbing multiple times as a little kid, thinking I will never get to get married, I will never get to have children. There’s no point in having any kind of dream for my future because I’ll be in heaven,” she said. “And then I would have guilt and shame, even as a little kid, because I’d know I was supposed to be happy about that.”

As a teen, Frazier participated in a youth group-sponsored hell house, a riff on haunted houses that portrayed sinful scenarios—like drunken car crashes and an abortion clinic—that led to hell.

Afterward, participants were invited to say the “sinner’s prayer.” Inundated with images of the terror she’d face if she wasn’t chosen by God, Frazier constantly was vigilant, ready to respond to disaster. But there was a cost.

“Humans aren’t meant to survive like that. Walking around with a fire extinguisher going all the time when there’s no fire is exhausting.”

Frazier paused her education after receiving her associate degree, in part because she thought Jesus would arrive at any time. Even when she had doubts, the risk of leaving her church community felt too high. She’d be forsaking her friends, her family and, later, as a parent, potentially jeopardizing her kids’ salvation.

“I’d be literally losing everything, for what? To go to college? Get a career?” she asked.

Fear of being ‘Left Behind’

April Sochia, 41, grew up in a Baptist community in the Adirondack Mountains of New York state and began to fear the rapture after reading the Left Behind series in college.

“I felt great pressure to force my kids to say the sinner’s prayer, because it was their ticket to heaven,” she said. “If the rapture happened, they had to say the sinner’s prayer, but it had to be genuine enough so they wouldn’t get left behind.”

According to Nikki, who now works as a certified trauma recovery coach, it’s common for people who believe in the rapture to evaluate and judge themselves constantly, seeking to be right with God so they won’t be judged harshly in the end times.

Andrew Pledger, 23, was part of the Independent Fundamental Baptist movement as a child in Walkertown, N.C., when his 4-H Club took a field trip to a local farm. Before the farm tour started, Pledger went to the bathroom. When he came out, no one was there.

“I remember just dread and fear going throughout all of me,” he said. “I couldn’t hear anyone’s voices, they were just gone. I remember running around the yard screaming and yelling for my mother … those five minutes of that fear and rapture anxiety, it was a lot.”

Though Pledger no longer believes in the rapture, his body remembers. Just over a month ago, a plane flew low over his current home in Greenville, S.C., and the sound—so familiar in the rapture genre—shocked him into fight or flight mode.

“It’s so frustrating, the cognitive dissonance of, I don’t believe in the rapture anymore, but I experienced that,” he told RNS.

Concept ‘read back’ into the New Testament

Therapist Karris said much like people experience phantom limbs, people can experience “phantom ideas” even after rejecting the idea of the rapture.

“That’s why it lasts so long, because we’re talking about it being in the tracks of the nervous system,” he said.

Of course, belief in the rapture doesn’t always translate into trauma. For some, the promise of being chosen by God and escaping the world’s troubles is profoundly reassuring.

Still, the fact that some experience severe consequences shouldn’t be downplayed, Karris asserted.

Tina Pippin, a professor of religion at Agnes Scott College in Decatur, Ga., said the rapture isn’t strictly biblical. It’s a concept that’s “read back” into New Testament passages, which get “sort of appropriated or misappropriated,” Pippin said, in Scriptures like 1 Thessalonians 4, which says that those who are “alive and are left” will “meet the Lord in the air.”

With 39 percent of American adults believing humanity is living in the end times, Pippin said, it’s important to assess the far-reaching implications of apocalyptic beliefs.

“The rapture is not just a theological position, it’s also a political one, and I think a really dangerous one,” said Pippin, who criticized those who ignore or even welcome global tragedies as precursors to Jesus’ return.

As awareness around rapture anxiety grows, many who’ve been impacted by rapture teachings are reassessing their beliefs and finding physical, emotional and spiritual healing.

During the height of the pandemic, Frazier stepped away from her church community. She still believes humans are “all divinely connected” and hopes to return to school to become a therapist.

For Grahn, the rapture panic she felt during the pandemic was the beginning of her faith unravelling. She no longer believes in Christianity or the rapture and holds space for religious trauma survivors on social media through her @apostacie accounts.

Her grandmother is still awaiting a heavenly ascent.

“I wouldn’t bring it up with my grandma. … They believe, as much as we know Christmas is on Dec. 25 every year, they believe it will happen at any moment,” said Grahn. “To them, it’s heaven or hell. They’re not going to give that up or take that chance.”

William “Bill” King Robbins Jr. of Houston, philanthropist and Baptist deacon, died April 13. He was 91. Robbins was born Nov. 29, 1931, to Helen and William King Robbins Sr. After he graduated from Robert E. Lee High School in Baytown, he earned Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Laws degrees from Baylor University and a Juris Doctor degree from Baylor Law School. In his early years, he served as an officer and director of various international subsidiary companies of Union Carbide Corporation and as legal counsel for Humble Oil and Refining Company, now Exxon Corporation. A Korean War veteran, Robbins was the founder and CEO of Houston-based North American Corporation, which engages in consulting, finance and investments, along with oil, gas and energy activities. He and his wife Mary Jo created the Robbins Foundation to support Christian missions causes, education and health care internationally. At Baylor University, their philanthropy supported institutional initiatives and scholarships to the Robbins Institute for Health Policy and Leadership within the Hankamer School of Business, as well as supporting Robbins Chapel within Brooks College. In March, Baylor dedicated the Mary Jo Robbins Clinic for Autism Research and Practice, named as part of a leadership gift by Bill Robbins in his wife’s honor. The clinic is housed within the Robbins College of Health and Human Sciences, named in recognition of a 2014 gift from the couple. “We are praying for Mary Jo, their family and so many in our Baylor community who had formed deep friendships with Bill over so many decades of support,” Baylor President Linda A. Livingstone said. “We mourn his passing, but we honor his life of service and the tremendous faith that guided and inspired him. The impact he leaves behind at Baylor is nothing short of transformational. He has supported, guided and exhorted our faculty and administration in the areas of healthcare and leadership, and the legacy that he and Mary Jo have created is truly humbling. Bill was renowned as a business leader and healthcare expert, but, most of all, he was known as a man of faith. What a powerful legacy.” At Baylor, Robbins was a member of the Endowed Scholarship Society, the Bear Foundation, the Old Main Society, the 1845 Society and the Heritage Club. He also was a life member of the Baylor Law Alumni Association. He served on the advisory councils of the Honors College and the Hankamer School of Business Robbins Institute for Health Policy and Leadership. He also was on the Robbins College of Health and Human Services board of advocates and the Baylor University Foundation board. He formerly served on the Baylor University board of regents and on the board of trustees at Baylor College of Medicine. He also supported Baylor Scott & White Medical Center-Hillcrest in Waco and the Baylor Louise Herrington School of Nursing in Dallas. Survivors include his wife Mary Jo Huey Robbins; children Cynthia K. Robbins, Jackson Gorman and wife Cheryl Scoglio, and Crystal Baird; and two grandchildren. Visitation is scheduled April 20 from 5 p.m. to 6 p.m. for the family and 6 p.m. to 8 p.m. in the Grand Chapel at Forest Park Lawndale Funeral Home in Houston. A memorial service will be at 11 a.m. on April 21 at Tallowood Baptist Church in Houston. Memorial gifts may be made to the Robbins Foundation, 4265 San Felipe, Suite 300, Houston, TX 77027 or to Tallowood Baptist Church, 555 Tallowood Rd, Houston, TX 77024.

William “Bill” King Robbins Jr. of Houston, philanthropist and Baptist deacon, died April 13. He was 91. Robbins was born Nov. 29, 1931, to Helen and William King Robbins Sr. After he graduated from Robert E. Lee High School in Baytown, he earned Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Laws degrees from Baylor University and a Juris Doctor degree from Baylor Law School. In his early years, he served as an officer and director of various international subsidiary companies of Union Carbide Corporation and as legal counsel for Humble Oil and Refining Company, now Exxon Corporation. A Korean War veteran, Robbins was the founder and CEO of Houston-based North American Corporation, which engages in consulting, finance and investments, along with oil, gas and energy activities. He and his wife Mary Jo created the Robbins Foundation to support Christian missions causes, education and health care internationally. At Baylor University, their philanthropy supported institutional initiatives and scholarships to the Robbins Institute for Health Policy and Leadership within the Hankamer School of Business, as well as supporting Robbins Chapel within Brooks College. In March, Baylor dedicated the Mary Jo Robbins Clinic for Autism Research and Practice, named as part of a leadership gift by Bill Robbins in his wife’s honor. The clinic is housed within the Robbins College of Health and Human Sciences, named in recognition of a 2014 gift from the couple. “We are praying for Mary Jo, their family and so many in our Baylor community who had formed deep friendships with Bill over so many decades of support,” Baylor President Linda A. Livingstone said. “We mourn his passing, but we honor his life of service and the tremendous faith that guided and inspired him. The impact he leaves behind at Baylor is nothing short of transformational. He has supported, guided and exhorted our faculty and administration in the areas of healthcare and leadership, and the legacy that he and Mary Jo have created is truly humbling. Bill was renowned as a business leader and healthcare expert, but, most of all, he was known as a man of faith. What a powerful legacy.” At Baylor, Robbins was a member of the Endowed Scholarship Society, the Bear Foundation, the Old Main Society, the 1845 Society and the Heritage Club. He also was a life member of the Baylor Law Alumni Association. He served on the advisory councils of the Honors College and the Hankamer School of Business Robbins Institute for Health Policy and Leadership. He also was on the Robbins College of Health and Human Services board of advocates and the Baylor University Foundation board. He formerly served on the Baylor University board of regents and on the board of trustees at Baylor College of Medicine. He also supported Baylor Scott & White Medical Center-Hillcrest in Waco and the Baylor Louise Herrington School of Nursing in Dallas. Survivors include his wife Mary Jo Huey Robbins; children Cynthia K. Robbins, Jackson Gorman and wife Cheryl Scoglio, and Crystal Baird; and two grandchildren. Visitation is scheduled April 20 from 5 p.m. to 6 p.m. for the family and 6 p.m. to 8 p.m. in the Grand Chapel at Forest Park Lawndale Funeral Home in Houston. A memorial service will be at 11 a.m. on April 21 at Tallowood Baptist Church in Houston. Memorial gifts may be made to the Robbins Foundation, 4265 San Felipe, Suite 300, Houston, TX 77027 or to Tallowood Baptist Church, 555 Tallowood Rd, Houston, TX 77024.

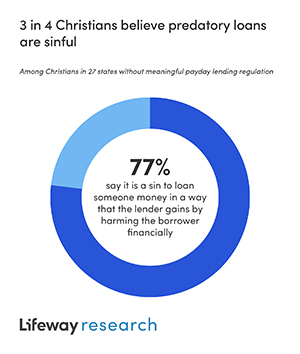

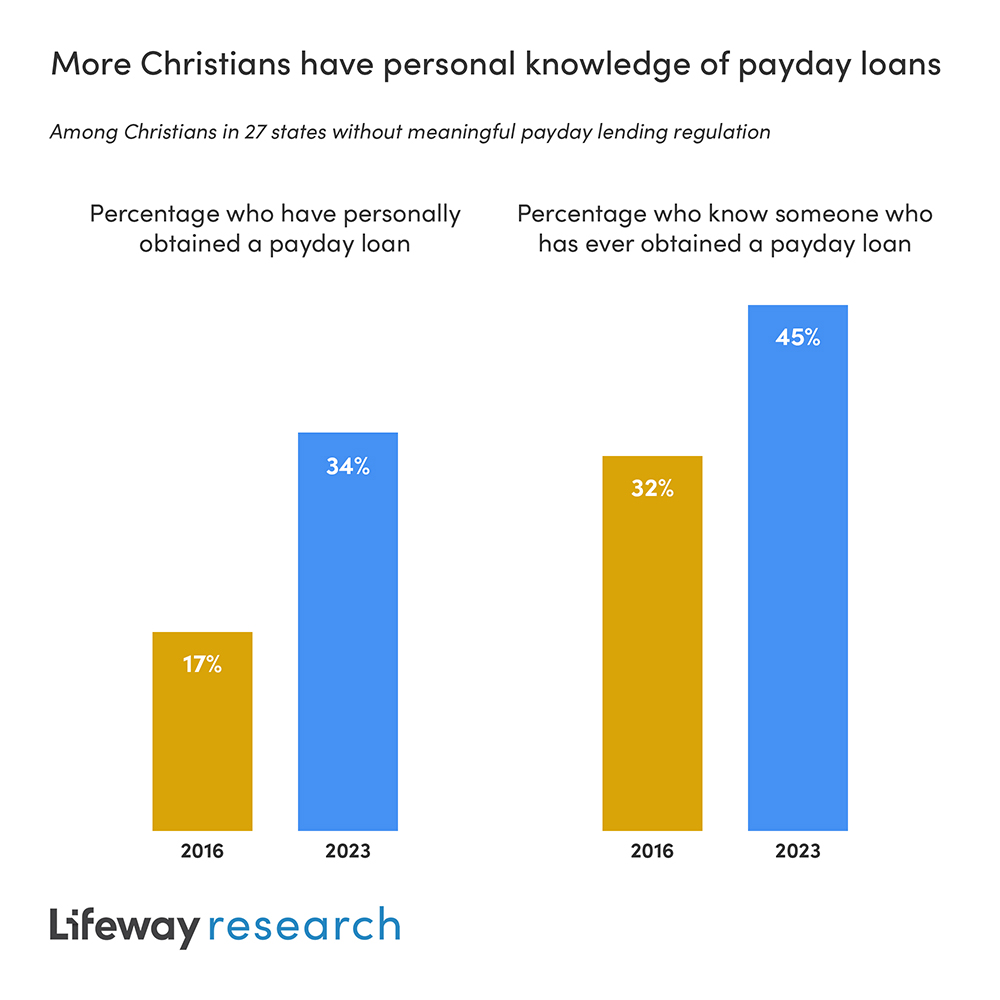

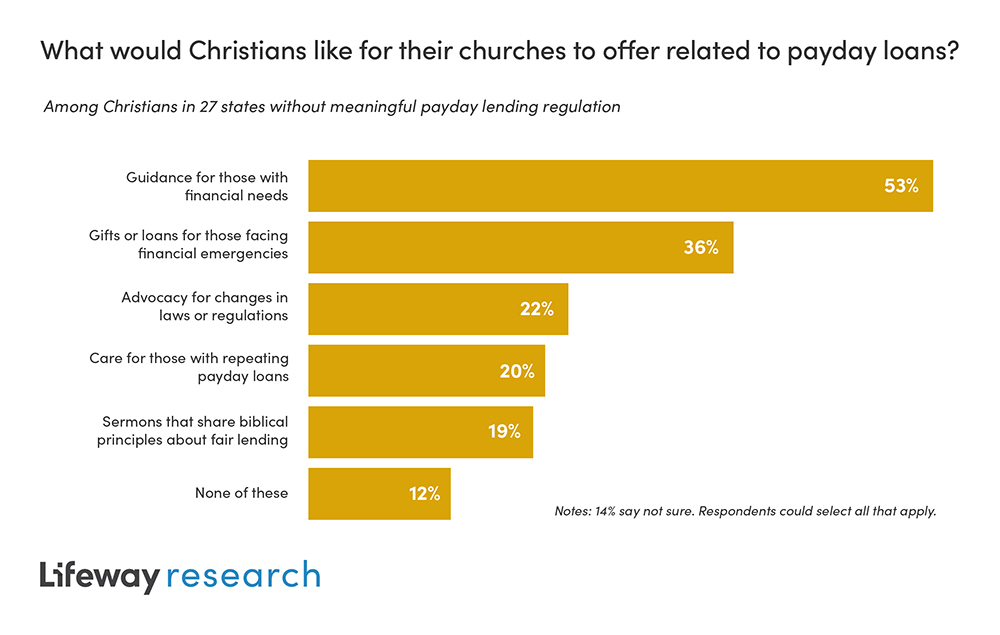

More than 3 in 4 surveyed Christians—77 percent—believe it is a sin to loan money in a way that the lender gains by harming the borrower financially, and most describe payday loans as expensive.

More than 3 in 4 surveyed Christians—77 percent—believe it is a sin to loan money in a way that the lender gains by harming the borrower financially, and most describe payday loans as expensive.

Ide P. Trotter, Baptist layman and a former dean and professor of finance at Dallas Baptist University, died April 4. He was 90. He was born Oct. 27, 1932, in Colombia, Mo., to Ide P. Trotter Sr. and Lena Ann Breeze Trotter. His family moved to the College Station area when his father became head of the Department of Agronomy at Texas A&M University, and he made a profession of faith in Christ at age 9 at First Baptist Church in Bryan. After graduating from Stephen F. Austin High School in Bryan, he enrolled at Texas A&M, where he began attending the campus chapter of InterVarsity Christian Fellowship. As a senior, he was chaplain of the Corps of Cadets and president of the Student Senate. He graduated as valedictorian of his class with both a commission as a 2nd Lieutenant in the U.S. Army and a National Science Foundation Fellowship to attend Princeton University, where he earned his doctorate. He completed his military service in the Chemical Corps School at Ft. McClellan in Alabama and worked for Humble Oil and Refining Company. While working in Baytown, he and his wife Luella taught a Sunday school class at First Baptist Church of Baytown. While he worked on a one-year assignment with Esso Research and Engineering Co. in New Jersey, his family was involved in helping a mission church established by Madison Baptist Church. His work in management at Humble Oil—and later Exxon—took him and his family first to Houston and then to Millings, Mont., and Stamford, Conn., where he was chairman of deacons at Greenwich Baptist Church. While in Tokyo, Japan, and he and his wife taught a Bible class for couples at Tokyo Baptist Church. While they were in Brussels, Belgium, he was chair of deacons at International Baptist Church. After completing his career at Exxon in 1986, he became dean of the College of Management and Free Enterprise and professor of finance at Dallas Baptist University, where he served until 1990. He served as a deacon and Sunday school department director at First Baptist Church in Dallas and as chair of the Dallas Life Foundation homeless shelter. He founded Trotter Capital Management, and he served as a spokesman for Texans for Better Science Education. He was also instrumental in helping establish the Trotter Prize and Endowed Lecture Series at Texas A&M University. He was preceded in death by his wife Luella. He is survived by daughter Ruth Penick and her husband Jim; daughter Reni Pratt and her husband Randall; daughter Cathy Trotter Wilson and her husband Kevin; 13 grandchildren; and his brother Ben.

Ide P. Trotter, Baptist layman and a former dean and professor of finance at Dallas Baptist University, died April 4. He was 90. He was born Oct. 27, 1932, in Colombia, Mo., to Ide P. Trotter Sr. and Lena Ann Breeze Trotter. His family moved to the College Station area when his father became head of the Department of Agronomy at Texas A&M University, and he made a profession of faith in Christ at age 9 at First Baptist Church in Bryan. After graduating from Stephen F. Austin High School in Bryan, he enrolled at Texas A&M, where he began attending the campus chapter of InterVarsity Christian Fellowship. As a senior, he was chaplain of the Corps of Cadets and president of the Student Senate. He graduated as valedictorian of his class with both a commission as a 2nd Lieutenant in the U.S. Army and a National Science Foundation Fellowship to attend Princeton University, where he earned his doctorate. He completed his military service in the Chemical Corps School at Ft. McClellan in Alabama and worked for Humble Oil and Refining Company. While working in Baytown, he and his wife Luella taught a Sunday school class at First Baptist Church of Baytown. While he worked on a one-year assignment with Esso Research and Engineering Co. in New Jersey, his family was involved in helping a mission church established by Madison Baptist Church. His work in management at Humble Oil—and later Exxon—took him and his family first to Houston and then to Millings, Mont., and Stamford, Conn., where he was chairman of deacons at Greenwich Baptist Church. While in Tokyo, Japan, and he and his wife taught a Bible class for couples at Tokyo Baptist Church. While they were in Brussels, Belgium, he was chair of deacons at International Baptist Church. After completing his career at Exxon in 1986, he became dean of the College of Management and Free Enterprise and professor of finance at Dallas Baptist University, where he served until 1990. He served as a deacon and Sunday school department director at First Baptist Church in Dallas and as chair of the Dallas Life Foundation homeless shelter. He founded Trotter Capital Management, and he served as a spokesman for Texans for Better Science Education. He was also instrumental in helping establish the Trotter Prize and Endowed Lecture Series at Texas A&M University. He was preceded in death by his wife Luella. He is survived by daughter Ruth Penick and her husband Jim; daughter Reni Pratt and her husband Randall; daughter Cathy Trotter Wilson and her husband Kevin; 13 grandchildren; and his brother Ben.