Election campaign makes some evangelicals reject name

WASHINGTON (RNS)—The head of the public policy arm of the nation’s largest Protestant denomination caused a stir this election season when he said he no longer wanted to be called an “evangelical Christian.” But an evangelical identity crisis has been simmering for some time.

Russell Moore, president of the Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention, sought to distance his own faith from the one surveyed at the polls or preached by televangelists promising riches as a reward for belief in God.

“Any definition that includes both a health and wealth prosperity gospel teacher and me is a word that’s so broad it’s meaningless,” he said.

Donald Trump, Republican presidential candidate, points to Liberty University President Jerry Falwall, Jr. after speaking in Lynchburg, Va., in January. Photo courtesy of REUTERS/Joshua RobertsFor Moore, evangelical leaders’ support for—or silence on—Republican candidate Donald Trump in the current presidential race was the last straw.

Donald Trump, Republican presidential candidate, points to Liberty University President Jerry Falwall, Jr. after speaking in Lynchburg, Va., in January. Photo courtesy of REUTERS/Joshua RobertsFor Moore, evangelical leaders’ support for—or silence on—Republican candidate Donald Trump in the current presidential race was the last straw.

For bloggers Micah J. Murray or Rachel Held Evans, who wrote about her struggles with the church in her 2015 book Searching for Sunday: Loving, Leaving and Finding the Church, it was the number of evangelical Christians who cancelled sponsorships for children in need after World Vision announced in 2014 it would employ people in same-sex marriages. The agency later reversed that decision.

Growing up in an evangelical family, she said, the word “evangelical” seemed synonymous with “real” or “authentic” Christian. But that changed.

“The World Vision incident confirmed what I’d been suspecting for a while—that my values were simply out of line with the evangelical culture’s values. And by then, I’d just grown weary of fighting for a label that no longer fit,” she said.

Deborah Jian Lee “If you look through evangelical history, conservatives and progressives have been in this tug of war about what it means to be evangelical,” said Deborah Jian Lee, author of Rescuing Jesus: How People of Color, Women and Queer Christians are Reclaiming Evangelicalism.

Deborah Jian Lee “If you look through evangelical history, conservatives and progressives have been in this tug of war about what it means to be evangelical,” said Deborah Jian Lee, author of Rescuing Jesus: How People of Color, Women and Queer Christians are Reclaiming Evangelicalism.

“People are either leaving and distancing themselves from the evangelical label, and others are staying and trying to change it.”

She puts herself in that first group, she said, along with a number of post-evangelical Christians she interviewed for “Rescuing Jesus” who now call themselves simply “Christian”—or by labels like “progressive Christian” or “spiritual, but not religious.”

Murray calls himself an “angsty, post-evangelical, progressive-ish Christian.”

These Christians maintain, “The gospel is for everyone—no exceptions,” Lee said. But, for many, evangelicalism has become about “rules and boundaries and who’s in and who’s out,” she said.

“That doesn’t sound like good news. That doesn’t sound like the message of the gospel,” Lee said.

Tracing history

It’s an age-old question, according to Lee: What is an evangelical?

Nobody agrees, she said. Some exclude black Protestants from the label, counting “black Protestant” as its own category in polls, although many would identify with beliefs considered evangelical, she said. Some measure behavioral benchmarks like Scripture reading and church attendance.

The Institute for the Study of American Evangelicals at Wheaton College in Wheaton, Ill., estimates the total number of evangelicals at up to 100 million Americans, she noted. Meantime, she said, the Pew Research Center puts that number closer to 62 million.

What is clear is the evangelical Christian movement “wields huge influence in America,” she said. That’s reflected in the polls and in how evangelical leaders shape policy and culture, she observed.

Larry EskridgeAnd that’s nothing new, said Larry Eskridge, former associate director of the Institute for the Study of American Evangelicals, which closed in 2014.

Larry EskridgeAnd that’s nothing new, said Larry Eskridge, former associate director of the Institute for the Study of American Evangelicals, which closed in 2014.

“These are hardly new arrivals in American culture. This is part of the makeup of the country,” Eskridge said.

The movement has its roots in the early church—from the Greek word “euangelion,” meaning “the good news”—and the Protestant Reformation. Martin Luther called his church the “evangelische Kirche,” or “evangelical church.”

It came to the United States, as the country declared its independence, with evangelists John Wesley, George Whitefield and Jonathan Edwards, Eskridge said. By the 1820s, evangelical Protestantism was the dominant form of Christianity in the United States, he said.

It split from fundamentalism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, wanting to be more engaged in the world and across Christian denominations, and it coalesced around places like Wheaton and the Moody Bible Institute in Chicago and people like Billy Graham, he said.

“To get that army to march to the beat of a single drum is nigh on impossible,” he said. And that confusion is showing now, as evangelicals try to hold their coalition together.

The problem with polling

Russell Moore isn’t ready to give up on the term “evangelical.” It’s a beautiful word, he said, and one that “we can and ought to reclaim.”

Part of the confusion is a misunderstanding by those outside the church of what “evangelism” means, Moore insisted. It becomes a political voting bloc in many media reports, he said.

And the religious right mobilized by the late Jerry Falwell and others has “done a good job of defining of what it means to be evangelical in the public sphere and the media” over the past 40 years, Lee said. That’s overshadowed the progressives who have been part of that sphere this whole time, she said. And it’s put off a number of Christians who previously identified as evangelical, Murray added.

“Donald Trump’s support among many evangelicals has brought these tensions to a head, and I’ve been encouraged to see evangelical leaders like Russell Moore begin preaching a gospel that transcends a single political party,” Evans said.

Instead of asking respondents if they identify as evangelical, the Barna Group asks whether they met nine specific theological criteria, such as whether they say their faith is very important in their lives, the Bible is accurate and sharing their religious beliefs with non-Christians is essential.

Moore agrees with that kind of approach. To be considered an evangelical, one should agree on theological positions and be actively engaged in a local congregation, he said.

But a Pew Research Center analysis released March 14 showed those who self-identify as “evangelical” or “born again” in its polling meet many of the same criteria tracked by Barna. They are more than twice as likely as other voters to attend church at least once a week, share their faith with others and agree that religion is “very important” in their lives and that the Bible is the literal word of God.

Shifts in evangelical culture

Part of the confusion over the term also is an identity crisis within evangelicalism, Moore said. The movement “often does a very poor job of maintaining its theological identity.”

“I think that’s changing because when one looks at what’s happening in the universities, in the seminaries, in the major conferences across the country, there’s an evangelicalism that is much more subconsciously, theologically aligned,” Moore said.

That’s not all subconscious, though. More careful attention to theology “has been necessitated by shifts in evangelical culture,” Moore said.

When agreement on cultural values was assumed, he said, evangelicals downplayed their unique beliefs—both with each other and with those outside the church.

But, Lee said, “The demographics of this country are changing rapidly, and the demographics of the church are following suit.”

Non-white Christians made up 19 percent of evangelicals in 2007, according to the Pew Research Center. By 2014, that number had increased to 24 percent.

Not only has the racial makeup of church people changed, but also the generational makeup, she said. Those communities are bringing their own values, and they’re offering competing visions for who is an evangelical, Eskridge said.

The “self-appointed leaders” of evangelicalism have been “conservative, white, straight” and male, and they view Scripture through that lens, Lee said. They may not understand there are many other segments of the church “that cherish Scripture just as much and love Jesus just as much and want to live that out in their lives—they just look different,” she said.

And younger generations of evangelicals tend to fall in the center of the political spectrum, shifting the emphasis to social justice issues, according to Eskridge. Even that isn’t entirely new to evangelicalism, he said: William Wilberforce, for one, helped lead the movement to end slavery in the United States.

“It’s been a contentious and puzzling question all along. So, in a lot of ways, this is nothing new, because it has spilled over so much into the cultural stereotypes and the public arena because of the political edge,” he said.

Defining ‘evangelicalism’

The most famous definition of evangelicalism—and the one many evangelicals and evangelical organizations like Moore, LifeWay Research and the National Association of Evangelicals continue to point back to—is the Bebbington Quadrilateral.

In 1989, David Bebbington of the University of Stirling in Scotland identified four characteristics that define evangelicals:

- Conversionism—a belief each person must experience a conversion and be born again.

- Activism—a need to express one’s belief in the gospel through action.

- Biblicism—a high regard for the Bible as the ultimate authority.

- Crucicentrism—an emphasis on Christ’s sacrifice on the cross.

“Evangelicalism is not some abstract ideology. It’s a commitment to the gospel that people who have submitted themselves to the lordship of Jesus Christ have made, including in their church lives,” Moore said.

There’s a “big tent” on issues that are considered secondary, he said. For instance, Moore is a committed Baptist, but he thinks a “believer’s baptism”—in which Christians are baptized after making a profession of faith, rather than as infants—is negotiable for evangelicals. There’s room for disagreement, too, on the nature of spiritual gifts or the role of women in the church, he said.

Evangelicals are “obsessed with Scripture,” Lee said, but there’s “diversity in how people interpret the text and how they should live out the gospel calling. That interpretation is very wide ranging.”

Rachel Held EvansEvans, for one, said she still believes the Bible is the authoritative word of God, faith is both personal and communal, and the gospel is worth sharing. And everything from the way she views Scripture to the things she gets nostalgic about remain rooted in her evangelical past, she said.

Rachel Held EvansEvans, for one, said she still believes the Bible is the authoritative word of God, faith is both personal and communal, and the gospel is worth sharing. And everything from the way she views Scripture to the things she gets nostalgic about remain rooted in her evangelical past, she said.

But she now goes to an Episcopal church, struggles with doubt and sometimes votes for Democrats. She also supports the full inclusion of gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender people in the church, and said she hates that evangelicalism has become synonymous with “anti-gay.”

Earlier this month, both she and Murray tweeted their responses to those questioning the label “evangelical” after Moore’s declaration.

“I suspect that most evangelicals would not identify me as ‘one of them.’ So, after a decade of trying to convince the culture I belong, I just dropped the label,” she said.

“Now I simply identify as a Christian.”

Emily McFarlan Miller is a national reporter for RNS.

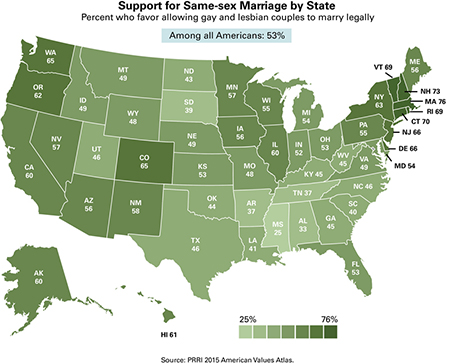

Even among groups that oppose same-sex marriage, support for protection from discrimination crosses all “partisan, religious, geographic, and demographic lines,” said Robert P. Jones, the institute’s chief executive officer.

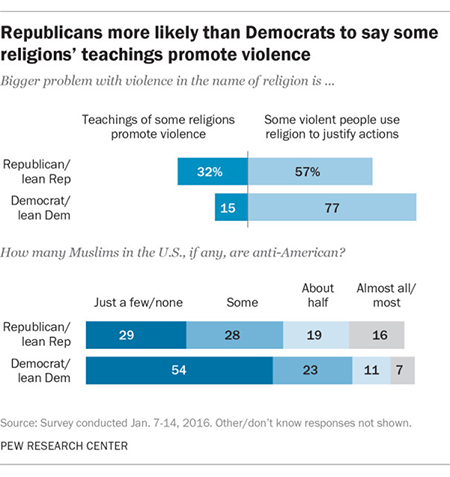

Even among groups that oppose same-sex marriage, support for protection from discrimination crosses all “partisan, religious, geographic, and demographic lines,” said Robert P. Jones, the institute’s chief executive officer. Among Democrats and those who lean Democratic, 54 percent say “just a few or no” Muslims here are anti-American. Thirty-four percent say this is so for about half or some Muslims in the U.S., and 7 percent say it’s true for almost all Muslims living here.

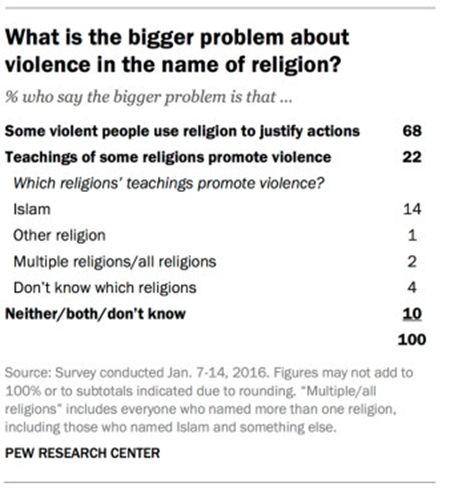

Among Democrats and those who lean Democratic, 54 percent say “just a few or no” Muslims here are anti-American. Thirty-four percent say this is so for about half or some Muslims in the U.S., and 7 percent say it’s true for almost all Muslims living here. According to the report, “Republicans are twice as likely as Democrats to say the main problem with violence committed in the name of religion is that some religions espouse violent teachings, although this is the minority view within both parties at 32 percent and 15 percent respectively.”

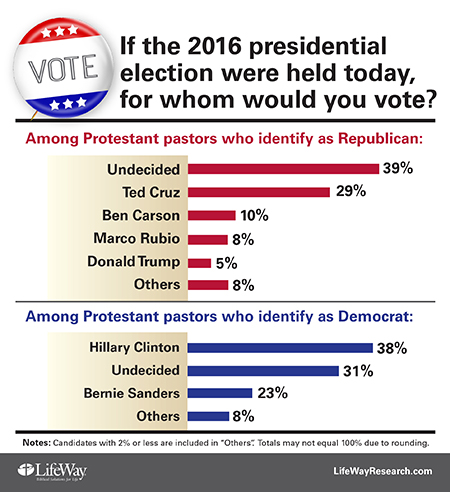

According to the report, “Republicans are twice as likely as Democrats to say the main problem with violence committed in the name of religion is that some religions espouse violent teachings, although this is the minority view within both parties at 32 percent and 15 percent respectively.” Among pastors who are Republicans, Cruz (29 percent) is in the lead, followed by Ben Carson (10 percent), Marco Rubio (8 percent) and Trump (5 percent). Thirty-nine percent are undecided.

Among pastors who are Republicans, Cruz (29 percent) is in the lead, followed by Ben Carson (10 percent), Marco Rubio (8 percent) and Trump (5 percent). Thirty-nine percent are undecided.