FORT WORTH (ABP)—An unusual controversy involving both ends of the “womb-to-tomb” spectrum of the sanctity of human life debate ended quietly Jan. 26 in a hospital in Fort Worth when doctors removed life support from a 33-year-old pregnant woman diagnosed as brain dead.

That ended a two-month legal battle for survivors of Marlise Muñoz, who was declared brain dead two days after her husband found her unconscious Nov. 26, possibly from a blood clot that traveled to her lungs.

That ended a two-month legal battle for survivors of Marlise Muñoz, who was declared brain dead two days after her husband found her unconscious Nov. 26, possibly from a blood clot that traveled to her lungs.

Doctors at John Peter Smith Hospital in Fort Worth had refused the family’s request to take Muñoz off a ventilator, because she was 14 weeks pregnant with the couple’s second child. They cited a 1999 Texas law that requires a pregnant woman to be kept on life support until her fetus is viable.

After doctors said the 22-week-old fetus was “distinctly abnormal,” casting doubt about its ability to survive outside the womb, state District Judge R.H. Wallace ruled Jan. 24 that Muñoz should be removed from life support.

“May Marlise Muñoz finally rest in peace and her family find the strength to complete what has been an unbearably long and arduous journey,” lawyers for her husband, Erick Muñoz, said in a statement reported in the media.

Right ro die

The case, along with another in California surrounding a 13-year-old girl who went into cardiac arrest after having her tonsils removed, reignited the debate over whether there is a right to die. The Muñoz dispute took on added weight, because it pitted the woman’s stated wishes not to be kept on life support against her baby’s right to be born.

“My opinion, based solely on news reports, is that both the family members and the judge were correct in their judgments in this case,” said David Gushee, distinguished university professor of Christian ethics at Mercer University serving this year as theologian-in-residence for the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship. “My heart goes out to the Muñoz family as they grieve their losses.”

“My opinion, based solely on news reports, is that both the family members and the judge were correct in their judgments in this case,” said David Gushee, distinguished university professor of Christian ethics at Mercer University serving this year as theologian-in-residence for the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship. “My heart goes out to the Muñoz family as they grieve their losses.”

While the U.S. Constitution doesn’t specifically mention a right to privacy, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1891 common law protects “the right of every individual to the possession and control of his own person, free from all restraint or interference of others, unless by clear and unquestionable authority of law.”

Sign up for our weekly edition and get all our headlines in your inbox on Thursdays

In 1914, the Supreme Court established the principle of “informed consent” in medicine, finding: “Every human being of adult years and sound mind has a right to determine what shall be done with his own body; and a surgeon who performs an operation without his patient’s consent commits an assault for which he is liable in damages.”

Early on, cases of patients refusing treatment were rare and usually involved medical practices forbidden by religious beliefs, also bringing the First Amendment into play. With advancements in medical technology allowing life to be sustained increasingly longer, however, the ethics of refusing treatment got more complicated.

The New Jersey Supreme Court determined in 1976 Karen Ann Quinlan, a young woman who suffered severe brain damage as the result of anoxia and entered a persistent vegetative state, could be taken off a respirator.

Right of privacy

The decision, left standing by the U.S. Supreme Court without review, established a right of privacy grounded in the federal Constitution to terminate treatment. The court recognized the right is not absolute, however, and must be balanced against asserted interest of the state.

In 1990, the high court refused to allow removal of artificial feeding and hydration equipment from Nancy Beth Cruzan, a Missouri woman who remained in a persistent vegetative state—a condition where a person exhibits motor reflexes but shows no evidence of cognitive function—seven years after a car wreck because her parents could not prove she would have wanted to die.

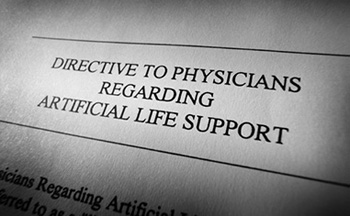

The Cruzan ruling sparked the movement of advance medical directives, including the living will, a legal document that spells out what kind of life-prolonging treatment an individual does or does not want. A medical power of attorney authorizes someone to make end-of-life decisions if you cannot make them yourself. Another advance directive is the do-not-resuscitate order, a request not to receive CPR if an individual goes into cardiac arrest.

Today, all 50 states have laws regarding an individual’s right to create an advance directive. In at least 31 of those states, however, according to a 2012 paper by the Center for Women Policy Studies, there is a pregnancy clause requiring life support to continue either until the fetus is declared not viable or the baby is born alive, even if the woman has indicated previously she does not want her life prolonged.

Today, all 50 states have laws regarding an individual’s right to create an advance directive. In at least 31 of those states, however, according to a 2012 paper by the Center for Women Policy Studies, there is a pregnancy clause requiring life support to continue either until the fetus is declared not viable or the baby is born alive, even if the woman has indicated previously she does not want her life prolonged.

Abortion rights also have been a moving target since the landmark 1973 Roe v. Wade decision establishing a woman’s right to have an abortion.

Prenatal life

While striking down most state laws at the time banning abortion, the Supreme Court acknowledged the state’s interest increases as prenatal life advances. Under Roe, a woman could seek an abortion freely in her first trimester, in an authorized clinic during the second trimester and states could prohibit abortions during the third trimester.

The Supreme Court abandoned the trimester framework in 1992, saying the state’s interest surpasses the woman’s rights at viability. In 1973 that was typically about 28 weeks of gestation but with advances in neonatal treatment had been reduced to about 23 or 24 weeks by the early 1990s.

Last year, Gov. Rick Perry signed a law pushing the cutoff back to 20 weeks, the time when some scientists say the fetus is developed enough to feel pain. That gave Texas one of the most restrictive abortion laws in the country. A federal judge blocked enforcement of the law, and a federal appeals court is in the process of deciding whether it is unconstitutional.

The Muñoz family said the 1999 law requiring a pregnant woman to be kept alive until her fetus is viable did not apply to her, because even though machines kept her breathing and her heart beating, she was not terminally ill but already dead.

Anti-abortion groups like Texas Right to Life and Operation Rescue campaigned to keep Muñoz hooked up to give her baby a chance at survival. NARAL Pro-Choice America petitioned Texas Attorney General Greg Abbot to respect the family’s wishes to remove her from life support.

We seek to connect God’s story and God’s people around the world. To learn more about God’s story, click here.

Send comments and feedback to Eric Black, our editor. For comments to be published, please specify “letter to the editor.” Maximum length for publication is 300 words.