The Mormon Moment

Nearly 200 years after religious zeal prompted a young convert named Joseph Smith to found a movement called the Latter-day Saints, the once-despised minority "cult" increasingly is going mainstream. With a Mormon running for president, a hit Broadway musical titled Book of Mormon and the now-rejected polygamy from the religious group's past forming the plotline of the long-running HBO series Big Love, evidence abounds of what has been termed the "Mormon moment."

For Baptists and other evangelicals trying to decide how to vote in the upcoming presidential election, it also has renewed discussion of whether the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is Christian.

The answer is complicated. If "Christian" means an individual who has placed his faith in the saving work of Jesus Christ, Mormons would seem to qualify. "I believe in a Heavenly Father; I believe in his Son Jesus Christ; I believe in the Holy Ghost," GOP presidential hopeful Mitt Romney has described his Mormon faith.

For 99 percent of the world's Christians, however, that Trinitarian formula refers to one God who exists as three distinct persons all described in the Bible. Mormonism holds a different view of the nature of God, has its own scriptures and is built on a presumption that revelation did not cease with the New Testament.

Many evangelicals object to calling Mormons "Christians" because of their theology and competition for converts, but even mainstream Presbyterians, Methodists and Lutherans do not recognize Mormon baptisms as valid.

Steven Harmon, an adjunct professor at Gardner-Webb Divinity School and author of Ecumenism Means You, Too, noted both the World Council of Churches and National Council of Churches of Christ in the USA do not consider the LDS eligible for membership.

|

"I am aware that the National Council of Churches, which is nothing if not an inclusive Christian organization, does officially classify relations with the LDS as interfaith rather than ecumenical," Harmon said.

Curtis Freeman, director of the Baptist House of Studies at Duke Divinity School, said the WCC requires members to subscribe to a basic Trinitarian confession of faith for membership.

"Originally it was simply the confession of 'Jesus is Lord,'" Freeman said. "That changed when the Orthodox joined. That alone excludes Mormons, who—though culturally Christian—are not Christian in any basic sense in doctrine."

Looking at "behavioral patterns," Mormons and evangelical Christians have a lot in common, said Tal Davis, a former interfaith consultant with the Southern Baptist Convention's North American Mission Board who is now with Market Faith Ministries.

"But to really answer the question about whether Mormonism is a Christian system, you really have to go a little deeper," Davis said in a June interview on Ed Stetzer's The Exchange online program. "You have to look at the doctrine. You have to look at the theology of Mormonism."

Kathleen Flake, a graduate of Brigham Young University who now teaches at Vanderbilt Divinity School, said most Christians encountering Mormonism find it a "mix of the familiar and the strange."

In a recent Christian Century article, Flake notes even Mormonism's most unfamiliar tenets rest in some way on the Bible, viewed as the word of God "insofar as it is translated correctly." Three other Latter-day Saints scriptures also are believed by Mormons to be God's direct revelation to Joseph Smith, the church's "founding prophet."

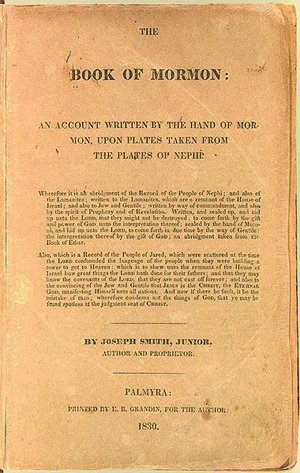

The Book of Mormon is a historical narrative covering a 1,000-year period that begins with the sixth century B.C. and ends in the fourth century after Christ. It includes an appearance by Jesus Christ to a remnant in the Americas shortly after his resurrection.

The Book of Doctrine and Covenants establishes church order related to church offices and temple worship and includes distinctive teachings such as proxy baptism for the dead.

The Pearl of Great Price includes the story of an event before creation when God meets with his children, and an argument develops about how creation should be ordered.

One character, Lucifer, advocates the use of force to ensure that humans will believe. Another advocates salvation through sacrifice and agrees to be the sacrifice as God's only Son. It is the back story for Mike Huckabee's question during a New York Times Magazine article in 2007, "Don't Mormons believe that Jesus and the devil are brothers?"

Another factor making Mormonism harder for outsiders to understand is that doctrine changes. The church's president claims to receive "continuing revelation" from God.

The LDS church officially abandoned polygamy, perhaps its most notorious legacy, in 1890, although it still shows up on fringes like sect leader Warren Jeffs, who was convicted of sexual assault on a child in a high-profile Texas case in 2011.

Kody Brown (center) stars in TLC's show Sister Wives with (left to right) multiple wives Robyn, Christine, Meri and Janelle. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints officially repudiated polygamy in 1890. (RNS FILE PHOTO/Courtesy TLC)

|

In 1998 LDS prophet Gordon B. Hinckley implied a shift in traditional Mormon teaching that human beings can become gods. Asked on Larry King Live whether Mormons believe God was once a man, Hinckley replied, "I wouldn't say that."

Dwight McKissic, pastor of Cornerstone Baptist Church in Arlington, sponsored an unsuccessful resolution at this summer's Southern Baptist Convention annual meeting calling on the SBC to repudiate racist teachings recorded in The Book of Mormon and The Pearl of Great Price that describe "skin of blackness" as "cursed," "loathsome," and justifiably derived as a result of a divine curse.

McKissic, who is African-American, said the resolution would "stop Mormon evangelism in its tracks" among people of color.

Kevin Smith, an African-American pastor who served as a member of this year's SBC resolutions committee, said members declined to bring a recommendation because they needed more research about whether or not the LDS officially repudiated the "curse of Ham" when it dropped its ban on ordaining black men to the priesthood in 1978.

"We are certainly alarmed at the inroads of Mormonism in all communities, and particularly in Africa," Smith said. However, "We do not want to call them to repent of something they have rejected."

Davis, co-author of the 1998 book Mormonism Unmasked, said the mainstreaming of Mormonism is a relatively recent phenomenon.

The LDS church used to emphasize the belief they are the one true church and all others are apostate. But Mormons have played it down as they have grown and spread outside of the West and worked alongside evangelicals on shared social issues like opposition to gay marriage.

"I think the LDS church now wants to present themselves as sort of a regular people," Davis said.

The church's latest advertising campaign profiles individuals from various walks of life giving testimonies titled "I'm a Mormon."

At the same time, Southern Baptist leaders have moved away from describing Mormonism as a "cult," preferring terms like "new religion."

"It's a term that I don't think is helpful," Ed Stetzer, head of LifeWay Research, said in the interview with Davis. "A cult is often thought of as a religious group with strange beliefs outside of the cultural mainstream."

"What you call Mormons today is what the world is going to call evangelical Christianity tomorrow, because increasingly we are a religious group with what the world sees as strange beliefs," Stetzer said.