NASHVILLE, Tenn.—Pastors have faced increased stress during the COVID-19 pandemic, as churches were forced to adapt overnight. More felt their role was overwhelming at times, but few pastors actually decided to leave the ministry.

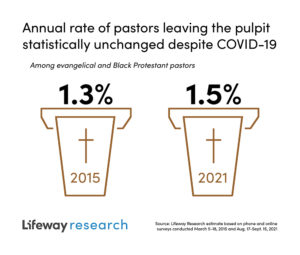

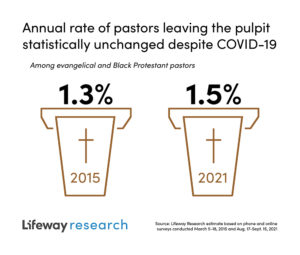

A new Lifeway Research study found close to 1 percent of evangelical and historically Black Protestant senior pastors step away from the pulpit each year—a rate statistically unchanged from a 2015 Lifeway Research study.

A new Lifeway Research study found close to 1 percent of evangelical and historically Black Protestant senior pastors step away from the pulpit each year—a rate statistically unchanged from a 2015 Lifeway Research study.

“COVID-19 was neither a small nor short-lived stressor for pastors,” said Scott McConnell, executive director of Lifeway Research. “Many have speculated that pastors have been opting out of the pastorate as a result. That is not the case. They are remaining faithful to the calling at levels similar to those seen before the pandemic.”

The August-September 2021 study surveyed more than 1,500 pastors serving in both evangelical and historically Black Protestant churches.

Around 1 in 6 pastors (17 percent) started at their current church during the pandemic years of 2020-2021. Half of the senior pastors facing the ministry upheaval brought on by COVID-19 were new to their role, and 51 percent are serving in their first church as senior pastor.

More than 1 in 3 pastors (37 percent) say they were the senior leader of their church 10 years ago. Among those congregations that had a different pastor in 2011, most of the previous pastors are now either retired (30 percent) or pastoring another church (28 percent).

In that time frame, some stepped away from the pulpit for a different ministry role (13 percent) or are working in a non-ministry position (8 percent), according to the current pastor. Combined, those two groups who leave the pastorate before retirement reveal an annual pastor attrition rate of around 1.5 percent.

“COVID-19 is not the only pressure pastors face, nor is it the most likely reason pastors from a decade ago are no longer pastoring,” McConnell said. “Baby Boomer pastors are reaching retirement age, and while many continue pastoring for years afterward, retirement is still the most common reason a pastor from 2011 is not pastoring a decade later.”

Thinking of their predecessor in cases where that person is working outside the pastorate, current senior pastors are most likely to say the previous pastor left due to a change in calling (32 percent), church conflict (18 percent), burnout (13 percent), being a poor fit with the church (12 percent), or family issues (10 percent).

Fewer point to a moral or ethical issue (8 percent), an illness (5 percent), personal finances (5 percent), or a lack of preparation (3 percent).

Conflict and change

Regardless of how the previous pastor left, the vast majority of pastors feel confident in their position. Nine in 10 pastors (90 percent) say they are sure they can stay at their current church as long as they want, including 60 percent who strongly agree.

While only 15 percent of pastors a decade ago have left the pastorate and fewer than 1 in 6 pastors say conflict drove that pastor from the pastorate, many pastors have experienced conflict in their church.

Among the pastors surveyed who pastored a different church previously, almost half (47 percent) say they left their last church because they took it as far as they could. Another third (33 percent) say their family needed a change. A quarter say there was conflict in the church (25 percent). More than 1 in 5 points to the church not embracing their approach to pastoral ministry (22 percent) or having unrealistic expectations of them (21 percent). Another 18 percent admit they were not a good fit for the church. Few say they were reassigned (14 percent) or asked to leave the church (10 percent).

Even if conflict didn’t cause them to leave their last church, most pastors (69 percent) say they dealt with some type of conflict there.

More than 1 in 3 say they experienced a significant personal attack (39 percent), had conflict over proposed changes (39 percent), or were in conflict with lay leaders (38 percent). More than a quarter ran into disagreements over expectations about the pastor’s role (28 percent) or their leadership style (27 percent). Fewer experienced conflict over doctrinal differences (12 percent) or politics (8 percent).

“Churches are groups of people, and even like-minded people do not always get along,” McConnell said. “It would be naïve to think a church would not experience disagreements. The important thing is whether that church maintains unity and love for each other as they navigate those differences or stoops to personal attacks as many pastors have experienced.”

Their previous experience with conflict leads 4 in 5 pastors (80 percent) to expect they will have to confront it in their current church in the future. As part of this preparation, 9 in 10 say they consistently listen for signs of conflict in their church (90 percent) and invest in processes and behaviors to prevent it (89 percent).

Overworked and overloaded

Direct conflict with churchgoers is not the only type of issue pastors face in their ministry. They often feel overworked and overloaded as individuals and worry about the toll their work may take on their family.

Most pastors say they are on-call 24 hours a day (71 percent) and their role is frequently overwhelming (63 percent). Half of pastors (50 percent) say the demands of their job are often greater than they can handle. Many say they feel isolated (38 percent) and face unrealistic expectations from their church (23 percent). One in 5 pastors (21 percent) admit they frequently feel irritated at their church members.

“The impact of the pandemic may be most noticeable in pastors’ increased agreement that the role of being a pastor is frequently overwhelming, which jumped from 54 percent in 2015 to 63 percent today,” McConnell said.

“But there has also been a shift in how some pastors think about their work. Fewer pastors agree they must be ‘on-call’ 24 hours a day, declining from 84 percent to 71 percent. Perhaps even more telling, the majority of pastors (51 percent) strongly agreed with this expectation in 2015, while only a third (34 percent) strongly feel this obligation today.”

Almost all evangelical and Black Protestant pastors are married (95 percent), and their role as spouse, and often parent, has the potential to conflict with their role as church leader. Most, however, feel serving in vocational ministry has been good for their family.

More than 9 in 10 pastors say their spouse is very satisfied with their marriage (96 percent) and enthusiastic about life in ministry together (91 percent). A similar percentage (94 percent) consistently protect time with their family. Most pastors were able to take a week’s vacation with their family last year (83 percent) and plan monthly date nights with their spouse (66 percent).

As a result, few say their work keeps them from spending time with their family (31 percent), and even fewer feel their family resents the demands of pastoral ministry (19 percent).

Still, 2 in 5 pastors say they are often concerned about their family’s financial security.

“Fewer pastors are concerned about their family’s financial security—41 percent today compared to 53 percent in 2015,” McConnell said. “This decrease in the number of pastors stressed over their personal finances may be due to increased generosity in their church or financial stimulus checks from the government. It is still more common for a pastor to be worried about their own finances than to report declines in giving at their church.”

Encouragement and support

While families may provide some added stress and responsibilities for pastors, they are also one of the sources of encouragement and support. They also are a channel through which a congregation can care for their pastor. Nine in 10 pastors (90 percent) say their family receives genuine encouragement from their church.

Close to 9 in 10 (86 percent) feel their church gives them the freedom to say no when faced with unrealistic expectations. While few say their church has a plan for the pastor to periodically receive a sabbatical (32 percent), almost 9 in 10 say they have a day to unplug from ministerial work and have a day of rest at least once a week (86 percent).

Pastors are also leaning on others for support and encouragement. Most say at least once a month they openly share their struggles with their spouse (82 percent), a close friend (68 percent), or another pastor (66 percent). Others say they are able to speak with lay leaders in the church (42 percent), a mentor (40 percent), another staff member (35 percent), a Bible study group in their church (23 percent), or a counselor (9 percent).

“The difficult moments and seasons pastors face require ongoing investment in their spiritual, physical and mental well-being,” McConnell said. “Most pastors and churches have practices that help the pastor in these ways, but there are often missed opportunities to encourage, build up and avoid misunderstandings.”

The study was sponsored by Houston’s First Baptist Church and Richard Dockins, M.D. The mixed mode survey of 1,576 evangelical and Black Protestant pastors was conducted Aug. 17–Sept. 15, 2021, using both phone and online interviews.

The completed sample is 1,000 phone interviews and 576 online surveys. Responses were weighted by region, church size and denominational group to reflect the population more accurately. The sample provides 95 percent confidence the sampling error does not exceed plus or minus 2.7 percent. Margins of error are higher in sub-groups.

Comparisons are made to a phone survey of 1,500 evangelical and Black Protestant pastors conducted by Lifeway Research March 5-18, 2015.

A new Lifeway Research study found close to 1 percent of evangelical and historically Black Protestant senior pastors step away from the pulpit each year—a rate statistically unchanged from a 2015 Lifeway Research study.

A new Lifeway Research study found close to 1 percent of evangelical and historically Black Protestant senior pastors step away from the pulpit each year—a rate statistically unchanged from a 2015 Lifeway Research study.

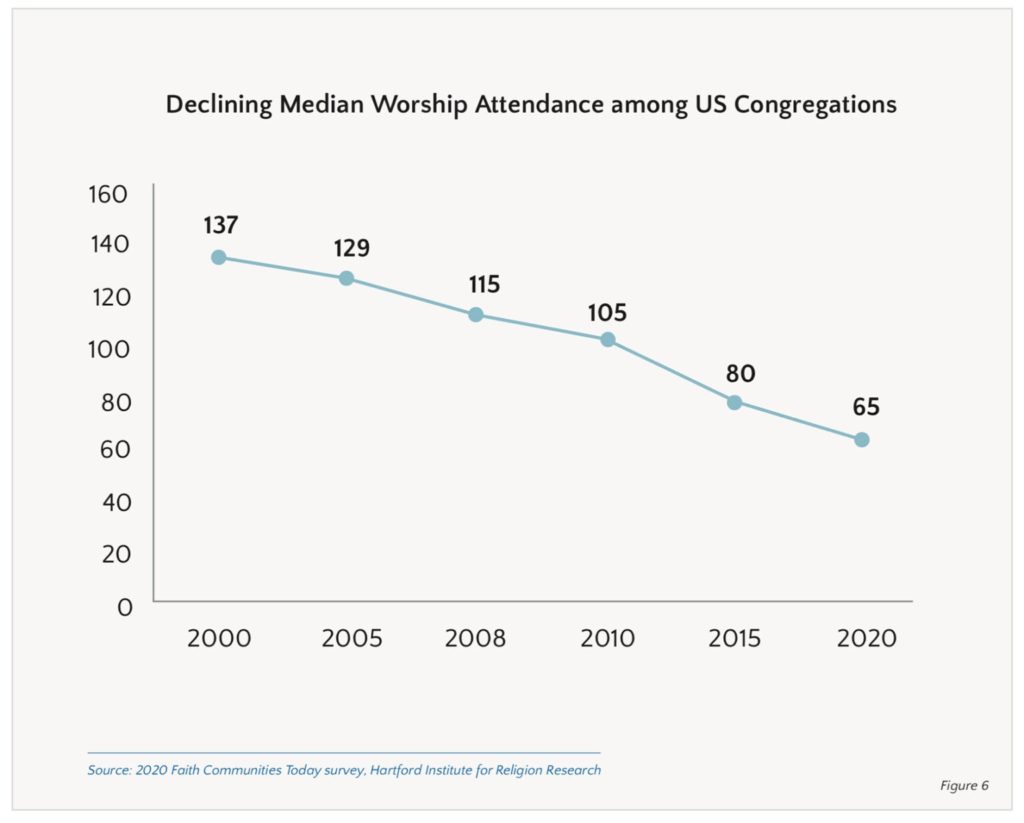

As Scott Thumma, director of the Hartford Institute for Religion Research and the survey’s author, put it: “The dramatically increasing number of congregations below 65 attendees with a continued rate of decline should be cause for concern among religious communities.”

As Scott Thumma, director of the Hartford Institute for Religion Research and the survey’s author, put it: “The dramatically increasing number of congregations below 65 attendees with a continued rate of decline should be cause for concern among religious communities.” In a

In a

The title is from the song Walk With Me, Lord. She was brutally beaten, nearly killed, in the Winona, Miss., jail in June of 1963. As she lay in her jail cell, bleeding and bruised and coming in and out of consciousness, she struggled to hang on and her cellmate, Euvester Simpson, a teenage civil rights worker, was there with her.

The title is from the song Walk With Me, Lord. She was brutally beaten, nearly killed, in the Winona, Miss., jail in June of 1963. As she lay in her jail cell, bleeding and bruised and coming in and out of consciousness, she struggled to hang on and her cellmate, Euvester Simpson, a teenage civil rights worker, was there with her. I don’t think I was aware how the two main Hebrew characters, Mordecai and Esther, were really clandestine in their faith initially. They blended into the culture, and they were happy to be thought of as Persian. They were so Persian, he could work for the king and she could sleep with the king, and nobody knew they were Jewish.

I don’t think I was aware how the two main Hebrew characters, Mordecai and Esther, were really clandestine in their faith initially. They blended into the culture, and they were happy to be thought of as Persian. They were so Persian, he could work for the king and she could sleep with the king, and nobody knew they were Jewish.