Did faith fall off a cliff during COVID? Not necessarily

WASHINGTON (RNS)—When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, many Americans lost the habit of churchgoing after almost every church in the country closed down in-person services and shifted online.

Did some of them give up on God? Sociologists like Michael Hout want to know.

Did some of them give up on God? Sociologists like Michael Hout want to know.

Hout, a professor of sociology at New York University, long has tracked the decline of organized religion in America. So, he was interested to see several indicators of what he called “intense religion” declined in the 2021 General Social Survey.

In that survey, fewer Americans than in 2016 said they take the Bible literally, pray frequently or have a strong religious affiliation. Even as church attendance consistently had been dropping off over the past decades, those more personal measures of faith had previously held steady or showed only slight decline.

“Then they fell off a cliff,” said Hout in a video interview.

Questions changes in survey format

In a new, yet-to-be-published study, Hout and colleagues Landon Schnabel from Cornell University and Sean Bock from Harvard, raise questions about the rapid decline in those measures during the pandemic, which they argue may be more due to changes in how the General Social Survey was administered rather than a sign of religious decline.

Founded in 1972 at the University of Chicago’s National Opinion Research Center, the General Social Survey, conducted every two years, has long been considered a gold standard for national surveys, in part because it has been administered in person rather than online or over the phone.

When the pandemic made in-person surveys unworkable, the General Social Survey switched to a hybrid approach, with most participants answering questions online, while others took the survey over the phone. Researchers also asked some of the participants in the 2016 and 2018 surveys to take part in the 2020 survey, which was published in 2021.

Hout and his colleagues compared past participants who agreed to retake the survey with those who did not and found that fewer “intensely religious” people retook the survey.

For example, they wrote, 36 percent of those who took part in the 2016 survey said they took the Bible literally. That dropped to 25 percent among those who completed the follow-up. They also found those who did not take the follow-up survey were more distrustful of institutions and more disconnected from civic society and the internet than those who did.

As a result, the change in survey format led to fewer religious people participating in the 2021 survey, which Hout believes skewed some of the results on religion.

That’s unfortunate, he said, especially at a time when the religious landscape in the United States is changing.

“If you want to measure change, don’t change how you measure it,” he said. “In this moment of great change, we changed how we measure it.”

Next survey will provide clearer picture

Hout said the 2022 General Social Survey data will give a clearer picture of how religion in the United States changed over the pandemic. And he hopes the General Social Survey will remain an in-person survey in the future, though he admitted doing in-person surveys is costly and difficult.

Overall, Hout said, surveys have become more difficult in recent years because of larger changes in American culture. In the past, he said, surveys offered ordinary people a way to comment on larger trends in the culture. Now, he said, social media allows everyone to speak their mind. And people are more skeptical about talking to strangers.

Overall, Hout said, surveys have become more difficult in recent years because of larger changes in American culture. In the past, he said, surveys offered ordinary people a way to comment on larger trends in the culture. Now, he said, social media allows everyone to speak their mind. And people are more skeptical about talking to strangers.

“Before the internet, one of the things that kept GSS and other survey response rates really high was the fact that people said, ‘Oh yeah, I’d love to get a few things off my chest,’” he said. “Now they have a lot of other options that they control much more of.”

A spokesman for the General Social Survey did not respond to a request for comment about changes in methodology.

Ryan Burge, assistant professor of political science at Eastern Illinois University and author of “The Nones,” believes a move online is inevitable for the survey. Burge, who often writes about religion and survey data, said most other major surveys, including those from Pew Research and the Cooperative Congressional Election Study, now have embraced online panels.

Burge believes online surveys give a more accurate view of religion in America than in-person interviews, in part because people are less likely to lie to a computer about their faith.

Being religious, he said, is still seen as a social good for many Americans. That leads to the so-called halo effect, where people overestimate how religious they are because they want to make a good impression on the surveyor.

Burge argues previous General Social Survey surveys have undercounted the number of Americans who are considered nones—those who have no religion. The 2021 survey, he said, gave a result more in line with other surveys, showing about 30 percent of Americans would be considered nones.

“People are more honest when they are looking at a web browser,” he said.

There are losses in the move from in-person to online surveys, Burge said. There is more nuance in an in-person interview, as people can give an answer that’s not on the survey. And not everyone understands all the denominational categories on surveys, he said, and might not know where they fit in an online survey.

Hout said that while organized religion in the United States is likely to continue to decline, much of the decline is among so-called Christians and Easter Christians, who only occasionally attend services.

That has led to what he called “all or nothing” approaches to religion—where people show up all the time and believe intensely, or they give up on religion. And people remain spiritual, even if they don’t identify with a particular faith.

“Atheism is not what’s happening,” Hout said. “If we think of organized religion as a conjoined thing, the quarrel is with the organized part, not the religion.”

Ahead of the Trend is a collaborative effort between Religion News Service and the Association of Religion Data Archives made possible through the support of the John Templeton Foundation.

“We should not miss the confrontational nature of this parable,” Keller writes in Forgive: Why Should I and How Can I? “Jesus’ parable about forgiveness is not a feel-good story about people receiving God’s forgiveness and then eagerly spreading the love to others. Rather, it is a story about a man asking for forgiveness and then being utterly unchanged when he got it.”

“We should not miss the confrontational nature of this parable,” Keller writes in Forgive: Why Should I and How Can I? “Jesus’ parable about forgiveness is not a feel-good story about people receiving God’s forgiveness and then eagerly spreading the love to others. Rather, it is a story about a man asking for forgiveness and then being utterly unchanged when he got it.”

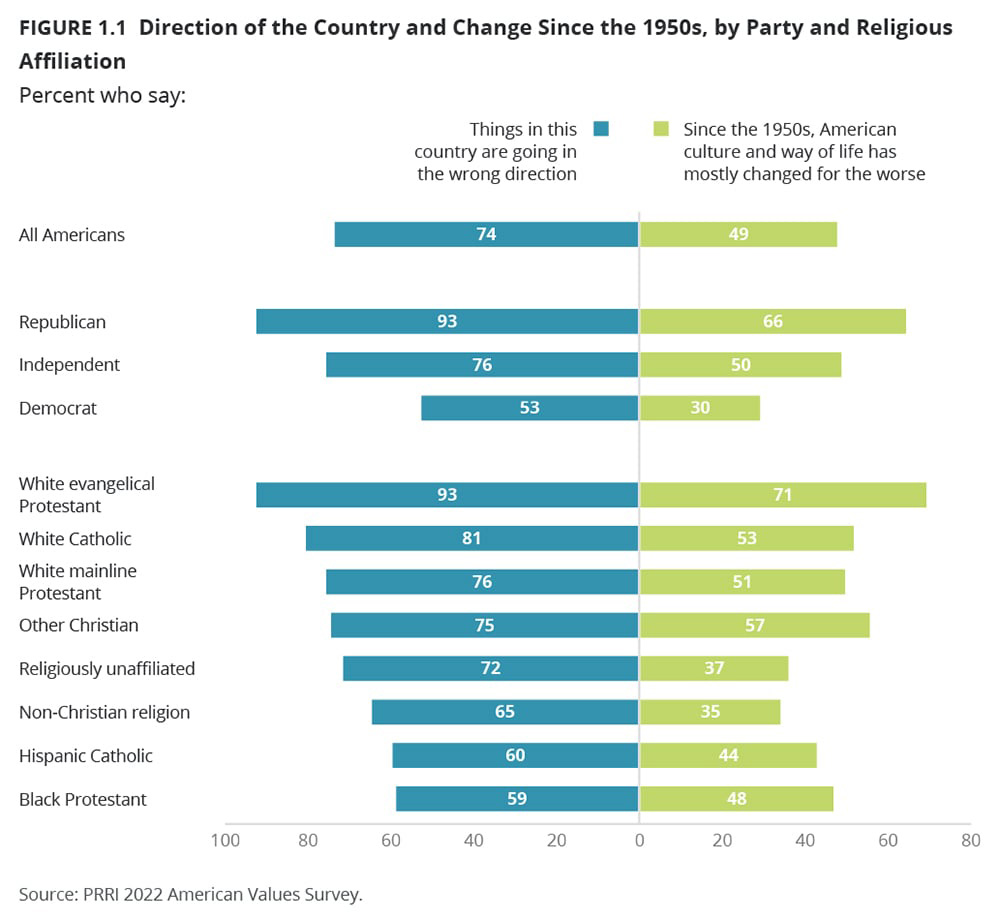

PRRI President Robert P. Jones, who discussed the survey Oct. 27 at Washington’s Brookings Institution, said the results are striking to him despite his spending years studying U.S. cultural and political patterns.

PRRI President Robert P. Jones, who discussed the survey Oct. 27 at Washington’s Brookings Institution, said the results are striking to him despite his spending years studying U.S. cultural and political patterns.