More Americans stay away from church since pandemic

WASHINGTON (RNS)—At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, nearly every congregation in the United States shut down, at least for a while. For some Americans, that was the push they needed to never come back to church.

A new report, which looked at in-person worship attendance patterns before the beginning of the pandemic and in 2022, found a third of those surveyed never attend worship services. That’s up from 25 percent before the start of the pandemic.

The pandemic likely led people who already had loose ties to congregations to leave, said Dan Cox, one of the authors of the new study and a senior fellow in polling and public opinion at the American Enterprise Institute.

“These were the folks that were more on the fringes to begin with,” said Cox. “They didn’t need much of a push or a nudge, to just be done completely.”

As part of the 2022 American Religious Benchmark Survey, researchers from the American Enterprise Institute and NORC at the University of Chicago asked 9,425 Americans about their religious identity and worship attendance. Those surveyed had answered the same questions between 2018 and early 2020.

Researchers then compared answers from between 2018 and 2020 to answers from 2022 to understand how attendance patterns changed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We are looking at the attendance patterns and religious identity of the exact same people at two different time periods,” said Cox.

The new study focused on attendance at in-person services versus online services. While some people—including the immunocompromised and their families—may still be attending digital services, measuring online engagement is “messier,” said Cox, and very different from in-person involvement. For example, he said, tuning in to a service for a few minutes is much different than going to a service in person.

Young adults particularly likely to skip church

The report also noted the decline in attendance most affected groups that had already started to show a decline before the pandemic—particularly among younger adults, who were already lagging before the pandemic and showed the steepest drop-off since.

Liberal Americans (46 percent), those who have never married (44 percent) and those under 30 (43 percent) are most likely to skip worship service altogether and saw the largest declines in attendance rates.

By contrast, conservatives (20 percent), those over 65 (23 percent) or those who are married (28 percent) are less likely to say they never attend services and saw less drop-off.

One in 4 Americans (24 percent ) said in 2022 that they attend regularly—which includes those who attend nearly every week or more often. Another 8 percent attend at least once a month—for a total of 32 percent who attend regularly or occasionally. That was down slightly from a total of 36 percent in 2020.

In 2022, just over a third (36 percent) said they attend at least once a year. Another third (33 percent) said they never attend—up from 25 percent in 2020.

Cox said generational shifts and the broader polarization in society likely played a role in the attendance decline.

Younger Americans are less likely in general to identify as religious or attend services—the 2021 General Social Survey found that 41.5 percent of Americans between 18 and 29 said they never attend services, with 20.6 percent saying they attend more than once a month.

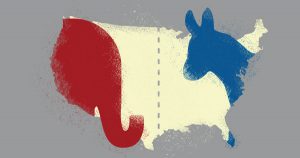

Political differences come to light

New political battlefronts also opened up during the pandemic, with vaccines and masks becoming points of contention and markers of political identity rather than public health interventions.

Conservative churches were likely to reopen sooner than more liberal congregations—making it easier for people to attend those churches in person.

The change in attendance patterns did not affect every group equally.

More than half of Latter-day Saints (72 percent) and white evangelicals (53 percent) said they attended service regularly in 2022, about the same rate as before the pandemic.

Other groups saw little drop-off in regular attenders as well, including Black Protestants (36 percent), white Catholics (30 percent), Hispanic Catholics (23 percent), white mainliners (17 percent) and Jews (10 percent), all reporting similar regular attendance rates in 2022 as before the pandemic.

The survey did show, however, that in most faith groups, the infrequent attenders were the largest group. That includes about half of white Catholics (46 percent), Hispanic Catholics (47 percent), white mainliners (51 percent) and Jews (54 percent).

Black Protestant regular attenders (36 percent) and infrequent attenders (35 percent) were about the same size.

Some hope in a dismal report

Cox found some hopeful news in the report, in that people have not given up their religious identity for the most part, even if they don’t attend. That gives religious leaders a chance to reconnect with larger numbers of people who still identify with religious traditions but don’t participate.

“These are the people who haven’t completely separated,” he said, so there is still a chance to reengage with them.

The folks who rarely attend services are also most at risk of disappearing completely. If that happens, churches and denominations would be in big trouble, said Cox.

“There are millions of people in that category,” he said. “If they go, I think it’s going to cripple a lot of a lot of denominations, and a lot of congregations are going to have to fold.”

Cox also worried about an increase in what he called “religious polarization,” between people who are active in religious congregations and those who have no involvement at all.

“We’re going to quickly come to a place where a good chunk of the country is not only going to have different views about religion, and different religious experiences, they’re not going to be able to relate to each other in any real way,” he said.

Reconnecting won’t be easy

Reengaging with people who have loose ties to churches will not be easy, said author and scholar Diana Butler Bass, who studies the changing religious landscape. Some people may prefer to attend services or engage spiritual practices online. Others have family challenges and aren’t able to attend.

And disputes over theology and liturgy can make it difficult to be part of a church.

Then there’s the human element.

Even before the pandemic, Americans were experiencing a loneliness crisis, with fewer spending time with friends or participating in social and civic activities. Many have lost the habits and skills of making friends and creating community, said Bass.

“Churches haven’t really figured that out,” she said. “They often say they are friendly but aren’t really—and lack ways of speaking about friendship theologically and developing friendship as a genuine practice of community.”

Many churches are struggling

The decline in attendance overall comes at a time when many congregations are struggling. The median congregation size in the United States dropped from 137 people in 2000 to 65 as of 2020, according to the Faith Communities Today study. Those Americans who do attend services often go to large congregations, leaving many smaller local churches and houses of worship in difficult straits.

Most congregations have seen attendance decline by about a quarter during the pandemic, said Scott Thumma, director of the Hartford Institute for Religion Research at Hartford International University.

That decline has hit smaller churches particularly hard. Most churches, he said, have fewer than 100 people. If 25 people are missing from those churches, that has a huge impact.

During the early days of the pandemic, Thumma said, churches innovated because they had to in order to survive. Now that the crisis of the pandemic has ebbed, they need to make long-term adaptations.

“What happened in the pandemic is that all of us were huddling in the basement, while a tornado was going over our heads,” he said. “Now everyone has come out of the basement and everything is completely different. Now we have to be intentionally creative.”

Churches also need to remind people of the importance of gathering together and to invite people to get involved in community outreach and other acts of service, said Thumma, such as volunteering for a food pantry or other ministry.

“Everything has to be hyper-intentional now,” he said.

While things are difficult, focusing on the future works better than just looking at things that are going wrong, said Thumma, who often consults with congregations and is the principal investigator in the long-term study Exploring the Pandemic Impact on Congregations.

“The focus should be, how can we become a better church—rather than, how do we re-create what we used to have?”

Ahead of the Trend is a collaborative effort between Religion News Service and the Association of Religion Data Archives made possible through the support of the John Templeton Foundation.

Christmas falls on a Sunday this year, and for most pastors, that gives them all the more reason to gather. More than 5 in 6 U.S. Protestant pastors (84 percent) say their church plans to have services on Christmas Day, a

Christmas falls on a Sunday this year, and for most pastors, that gives them all the more reason to gather. More than 5 in 6 U.S. Protestant pastors (84 percent) say their church plans to have services on Christmas Day, a  “Some churches meet on New Year’s Eve for a service followed by fun and fellowship,” McConnell said. “Others have a late-night or watchnight service reflecting on the past year with spiritually significant times of prayer and observing communion.

“Some churches meet on New Year’s Eve for a service followed by fun and fellowship,” McConnell said. “Others have a late-night or watchnight service reflecting on the past year with spiritually significant times of prayer and observing communion.

“That’s really harmful, because it used to be the case that when you’d go to church, you’d sit next to someone who’s a Republican, someone who’s Democrat, and you’d get a little bit of cross-cutting discussion going,” he said. “That’s not happening anymore.”

“That’s really harmful, because it used to be the case that when you’d go to church, you’d sit next to someone who’s a Republican, someone who’s Democrat, and you’d get a little bit of cross-cutting discussion going,” he said. “That’s not happening anymore.”