Young Calvinists at a crossroads after Keller’s death

WASHINGTON (RNS)—As a 7-year-old, Wyatt Reynolds prayed nightly before bed. He went to church faithfully in his south Georgia community but was never convinced that he had truly given his heart to Jesus.

Then, barely a teen, Reynolds began listening on his iPod Nano to a daily radio show run by Al Mohler, president of Southern Baptist Seminary, and went on to read the works of John Piper, R.C. Sproul and other contemporary Reformed Christian theologians and pastors. Through them, he found and embraced Calvinist doctrines.

“That was super liberating for me as an incredibly angsty middle schooler,” said Reynolds, now a Ph.D. candidate at Columbia University in New York.

Young, Restless and Reformed

Reynolds had joined the ranks of the “Young, Restless and Reformed”—a renewal movement born in the early 2000s and fueled by scores of his evangelical Christian peers who had grown up with largely theology-free, self-help-oriented sermons and fundamentalist shibboleths of evangelical churches.

Instead, these young Christians drank deeply of a theology named for the 16th-century French Protestant John Calvin that was brought to America by the Puritans.

At the time Reynolds joined, the Calvinist renewal movement was a juggernaut that generated a seemingly endless stream of conferences, books, videos and social media posts.

As charismatic and intellectual as they were conservative, its leaders touted countercultural ideas such as complementarianism—the belief that, while the sexes are equal, God put men in charge of the church and the home. Reformed renewal became a powerful lifestyle brand that united Christians across denominations and generations.

With that success came spectacular failures. In the 2010s, many of the movement’s leaders fell from grace. Mark Driscoll, founder of the now-shuttered Seattle megachurch Mars Hill, was accused of abusive behavior. Prominent pastor Tullian Tchividjian admitted to sexual misconduct. C.J. Mahaney was accused of covering up abuses in his church network. James MacDonald was terminated for a “substantial pattern of sinful behavior.”

Joshua Harris, whose bestselling 1997 book I Kissed Dating Goodbye was a bible of the purity culture, has left the Christian faith altogether.

This spring, the movement suffered another blow with the death of Tim Keller, a retired New York megachurch pastor, bestselling author and co-founder of The Gospel Coalition, one of the flagship institutions of the Reformed resurgence. Known for his intellectual curiosity and personal kindness, Keller was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in 2020 and died in late May.

While the movement remains influential, the controversies and losses raise questions about its future.

“What happens when you wake one morning and realize that if something’s going to be reformed,” said author and speaker Hannah Anderson, who was heavily influenced by the Reformed resurgence, “you’re the target of the reforming?”

‘Like water to thirsty people’

Anderson said she first encountered Calvinist theology as a college student through Minnesota pastor Piper’s 1986 book Desiring God. She’d come from a fundamentalist background where the overwhelming message was that a person never could be good enough to earn God’s love.

In Calvinism, she found a doctrine of salvation—“soteriology,” as theologians put it—that said it was God whose act of bestowing grace saved people, not human effort.

“Anything that spoke of grace was revelatory,” she said. “The grace part of reformed soteriology felt like water to thirsty people.”

As the movement grew, aspiring pastors began to flock to seminaries that taught the so-called doctrines of grace. Mohler’s Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Ky.; The Master’s Seminary in Los Angeles; and Piper’s Bethlehem College and Seminary in Minneapolis began churning out so many young, zealous pastors that the movement made national headlines.

Author Collin Hansen, whose 2008 book Young, Restless, Reformed chronicled the movement’s early days, explained Calvinism’s appeal to young Christians to Time magazine in 2009, saying, “They have plenty of friends: what they need is a God.”

Author Wendy Alsup, a longtime member of Mars Hill Church in Seattle, said she was drawn to the church’s surprising pairing of intellectual rigor and approachability. This approach translated into a veneer of sophistication.

“At the time, it meant that you could dress more hipster and drink beer, as opposed to a lot of the fundamentalist upbringing I had,” said Alsup.

But most importantly, many of those who encountered Calvinism around this time say their faith suddenly blossomed under its influence. Former Southern Baptist Convention President J.D. Greear said in a recent interview that, growing up, his understanding of God was “too small.” He struggled to give God the kind of devotion the Bible demanded, Greear said, which left him bewildered.

Things began to change after he read The Religious Affections by the Puritan writer Jonathan Edwards, who described a God big enough to commit his soul to—bigger than the figure who appeared in the seeker-friendly megachurches he’d grown up in.

“There was something about the Reformed presentation of the gospel that rang deeply in our hearts,” he said. “Because this was the God that had been talked about through all of the Bible stories we’d been hearing.”

‘Snack-size theological instruction’

Like the original Reformation of the 1500s, which advanced on the strength of the printing press, the new Reformed Christians were bolstered by a revolution in publishing. The internet allowed web-based apologists such as The Gospel Coalition, whose site draws 10 million viewers a year in the U.S. alone, to issue a constant stream of arguments.

Kristin Du Mez, professor of history at Calvin University and author of the 2022 bestseller Jesus and John Wayne, said the movement made Calvin’s tortuously layered doctrines accessible.

“It was kind of a snack-size theological instruction and very accessible, very popular for that reason,” she said. “But with a sense of being a weightier take.”

The resurgence also benefited from more traditional formats. In 2001, Crossway published the English Standard Version, a new Bible translation that used traditional terms such as “mankind” and “men” to denote human beings and favored a complementarian reading of the Scriptures.

Its success backed a publishing empire, according to Joey Cochran, an American religious historian and editor of the Anxious Bench blog at Patheos.com.

In this, Cochran sees a resemblance to Dispensationalism, an end-times theology based on the work of John Nelson Darby that popularized the concept of the Rapture in the early 1900s. Dispensationalism also had its own Bible—the Scofield Study Bible. It spread through radio broadcasts, the new tech of the time, and low-cost print publishing.

Similar to Dispensationalism, whose Rapture theology is now widely considered a core biblical belief among many evangelicals, new Calvinism used its network to plant ideas such as complementarianism firmly in the evangelical conversation.

Popular conferences created community

But perhaps nothing created the Calvinist phenomenon more than conferences. Thousands of young evangelicals like Greear found each other through events run by organizations such as Together for the Gospel—known as T4G—and The Gospel Coalition.

They forged long-term friendships and cooperation across denominational lines that continued as they gained pulpits across the United States.

That sense of community is typical of evangelical renewal movements, Du Mez said. Baptists, Calvinists and even some charismatic Christians saw Reformed theology as a unifying force, regardless of the theological traditions of their denominations.

Another hallmark of the Reformed resurgence was its development of scores of new congregations and a relentless desire among its adherents to spread the gospel.

Molly Worthen, a religious historian at the University of North Carolina, experienced that relentlessness firsthand while writing last year about the Summit Church, Greear’s North Carolina megachurch.

“There are few things that humans find more exciting than feeling like they are part of an unstoppable movement,” Worthen wrote.

Worthen, who credits Greear and Keller for her unexpected conversion to evangelical Christianity last summer, said the two men’s beliefs that ideas matter—and that Christianity had intellectual rigor—helped open the door to that conversion.

Intellectual gravity

She suspects intellectual curiosity plays a role in the influence of the Reformed resurgence movement and The Gospel Coalition.

“I think there is a fusion there in The Gospel Coalition—which, of course, Keller helped to found—that combines emphasis on mission with this intellectual gravity and this commitment to serious conversation about ideas that I think people in general are hungry for,” she said.

Brad Vermurlen, a research associate in the sociology department of the University of Texas and author of Reformed Resurgence: The New Calvinist Movement and the Battle Over American Evangelicalism, believes the movement’s influence outpaced its actual numbers.

New Calvinists came to “represent the center of influence and excitement within the American evangelical landscape,” he said, but in recent years, the movement has declined in “prominence, excitement and energy.”

Lack of mentoring young leaders

While the renewal identified charismatic leaders and gave them platforms, it did not do a good job of mentoring those leaders, Reynolds said. While attending The Journey, an influential Reformed church in St. Louis, he saw the church’s pastor, Darrin Patrick, fired in 2016 for misconduct.

“There wasn’t real mentorship of up-and-coming people,” said Reynolds. “There’s a way in which, if someone said they were called, looked good in skinny jeans and could quote someone who was dead, and pop culture, then you could be a leader.”

Anderson said she regrets the movement wasn’t Calvinist enough. She believes the movement focused mainly on salvation but missed a broader emphasis on common grace and the goodness of God’s creation. Those ideas—that God is at work everywhere and not just among an elect few—matter.

‘Pride was the downfall’

For some leaders, she said, that lack of balance led to a certainty of belief that lacked kindness toward anyone who disagreed.

Alsup said pride also became a downfall for some leaders in the Reformed resurgence, who believed their theology was better than the theology of other Christians.

Though Mars Hill members didn’t refer to themselves as “new Calvinists,” according to Alsup, when Mars Hill was at its best, members were comforted by Calvinist doctrines like irresistible grace, God’s sovereignty and the perseverance of the saints, which teach that “once God’s got you, he will keep you,” said Alsup.

But Mars Hill’s foundation began to crack. Driscoll was hit with accusations of plagiarism, profanity, sexual fixation, abuse of power and promoting an aggressive brand of machoism.

While Driscoll’s downfall has been attributed to many factors, Alsup points to an arrogance that she said many church members shared.

“We thought we were doing something new for God,” she said. “And we despised the generation that came before us. And the pride was the downfall.”

In the years since Mars Hill imploded, Alsup has found herself at a small, multicultural church plant in the Presbyterian Church in America.

“I kept the Reformed, but shook off the young and restless,” she quipped.

Keller, Alsup said, represented the best of the new Calvinist movement. He effectively communicated God’s greatness and grace, exuding kindness while probing constantly with his mind.

“It will be interesting to see, does it survive without someone like Tim?” Alsup said. “Have enough folks learned things from Tim to carry on the mantle of making it not threatening, but beautiful?”

He chose to probe the deep questions those issues raise through the fictional characters he brought to life in Bastille Day.

He chose to probe the deep questions those issues raise through the fictional characters he brought to life in Bastille Day.

But rarely, Tisby said, do Christians manage to overcome racial differences. In The Color of Compromise, Tisby recounts how English settlers in Virginia faced a dilemma. In their homeland, Tisby writes, the custom was to free slaves who converted to Christianity. In 1667, the Virginia General Assembly decided that, no matter what the Christian faith taught, baptism would not make slaves free.

But rarely, Tisby said, do Christians manage to overcome racial differences. In The Color of Compromise, Tisby recounts how English settlers in Virginia faced a dilemma. In their homeland, Tisby writes, the custom was to free slaves who converted to Christianity. In 1667, the Virginia General Assembly decided that, no matter what the Christian faith taught, baptism would not make slaves free. Despite saying they want to serve people who are not a part of their church, few churchgoers are even serving within the context of their own churches. Two in 3 (66 percent) churchgoers say they have not volunteered for a charity (ministry, church or non-ministry) in the previous year. Three in 10 (30 percent) say they have, and 4 percent are not sure.

Despite saying they want to serve people who are not a part of their church, few churchgoers are even serving within the context of their own churches. Two in 3 (66 percent) churchgoers say they have not volunteered for a charity (ministry, church or non-ministry) in the previous year. Three in 10 (30 percent) say they have, and 4 percent are not sure.

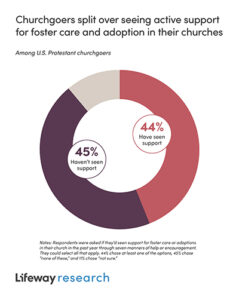

A similar percentage (45 percent) say they haven’t seen other churchgoers or leaders provide any of the specific types of care or support, while 11 percent aren’t sure.

A similar percentage (45 percent) say they haven’t seen other churchgoers or leaders provide any of the specific types of care or support, while 11 percent aren’t sure.

More than three-quarters of those who pray use at least one spiritually related object when they do.

More than three-quarters of those who pray use at least one spiritually related object when they do. “It’s not that we’re making new discoveries about women. It’s not that we’re trying to rewrite history. It’s simply that women have been obscured, and women’s actual roles in the Bible have been obscured,” said Beth Allison Barr, the James Vardaman Professor of History at Baylor University and author of The Making of Biblical Womanhood: How the Subjugation of Women Became Gospel Truth.

“It’s not that we’re making new discoveries about women. It’s not that we’re trying to rewrite history. It’s simply that women have been obscured, and women’s actual roles in the Bible have been obscured,” said Beth Allison Barr, the James Vardaman Professor of History at Baylor University and author of The Making of Biblical Womanhood: How the Subjugation of Women Became Gospel Truth.

Georgetown University’s Center on Faith and Justice held a virtual event April 26 to mark 60 years since King penned the letter on April 16, 1963, after being jailed for his organization of a nonviolent demonstration on Good Friday that year in the Alabama city. The letter was released publicly the next month and was included in his 1964 book Why We Can’t Wait.

Georgetown University’s Center on Faith and Justice held a virtual event April 26 to mark 60 years since King penned the letter on April 16, 1963, after being jailed for his organization of a nonviolent demonstration on Good Friday that year in the Alabama city. The letter was released publicly the next month and was included in his 1964 book Why We Can’t Wait.