Churches struggle to deal with suicide

NASHVILLE (BP)—Suicide remains a taboo subject in many Protestant churches, despite the best efforts of pastors, a new study by LifeWay research reveals.

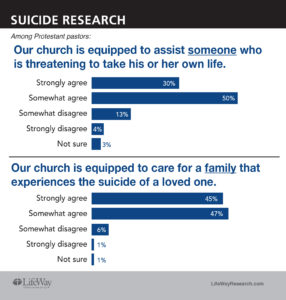

Eight in 10 Protestant senior pastors believe their church is equipped to intervene with someone who is threatening suicide, according to a study released Sept. 29 from LifeWay Research. Yet few people turn to the church for help before taking their own lives, according to their churchgoing friends and family.

Only 4 percent of churchgoers who have lost a close friend or family member to suicide say church leaders were aware of their loved one’s struggles.

“Despite their best intentions, churches don’t always know how to help those facing mental health struggles,” said Scott McConnell, executive director of LifeWay Research.

A common tragedy

Suicide remains a commonplace tragedy, according to data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. More than 44,000 Americans took their own lives in 2015, the most recent year for which statistics are available.

Suicide is the second leading cause of death for Americans ages 15 to 34 and the fourth leading cause of death for those 35 to 44.

LifeWay Research found suicide often affects churches. Researchers surveyed 1,000 Protestant senior pastors and 1,000 Protestant and nondenominational churchgoers who attend services at least once a month, in a study sponsored by the American Association of Christian Counselors, Liberty University Graduate Counseling program, the Liberty University School of Medicine and the Executive Committee of the Southern Baptist Convention.

LifeWay’s study found three-quarters (76 percent) of churchgoers say suicide is a problem that needs to be addressed in their community. About a third (32 percent) say a close acquaintance or family member has died by suicide.

Those churchgoers personally affected by suicide were asked questions about the most recent person they know who has died by suicide. Forty-two percent said they lost a family member, and 37 percent lost a friend. Others lost a co-worker (6 percent), social acquaintance (5 percent), fellow church member (2 percent) or other loved one (8 percent).

About a third of these individuals who died by suicide (35 percent) attended church at least monthly during the months prior to death, according to their friends and family. Yet few of those friends and family say church members (4 percent) or church leaders (4 percent) knew of their loved one’s struggles.

Caring responses

When a suicide occurs, churches often respond with care and concern to survivors. About half of churchgoers affected by suicide say their church prayed with the family afterward (49 percent). Forty-three percent say church members attended their loved one’s visitation or funeral. Forty-one percent say someone from the church visited their family, while 32 percent received a card.

Churches also provide financial help (11 percent), referral to a counselor (11 percent) and help with logistics like cleaning and child care (10 percent) or planning for the funeral (22 percent).

Still, churchgoers have mixed responses to suicide.

Overall, 67 percent of churchgoers say the loved ones of a suicide victim are treated the same as any other grieving family. Eighty-four percent say churches should provide resources to people who struggle with mental illness and their families. And 86 percent say their church would be a safe, confidential place to disclose a suicide attempt or suicidal thoughts.

Overall, 67 percent of churchgoers say the loved ones of a suicide victim are treated the same as any other grieving family. Eighty-four percent say churches should provide resources to people who struggle with mental illness and their families. And 86 percent say their church would be a safe, confidential place to disclose a suicide attempt or suicidal thoughts.

Yet churchgoers are aware friends and family of a person who dies by suicide can be isolated from the help they need because of the stigma of suicide. That can be true inside and outside the church, according to the survey.

More than half (55 percent) of churchgoers say people in their community are more likely to gossip about a suicide than to help a victim’s family. And few churchgoers say their church takes specific steps to address suicide or has resources to assist those experiencing a mental health crisis.

A quarter (24 percent) of churchgoers say their church has shared a testimony in the past year of someone who has struggled with mental illness or thoughts of suicide. Fewer (22 percent) say the church has used sermons in the past year to discuss issues that increase the risk of suicide.

Thirteen percent say their church has taught what the church believes about suicide, while 14 percent say the church trained leaders to identify suicide risk factors. Thirteen percent say their church shared reminders about national resources for suicide prevention.

Churches are most likely to offer prayer support (57 percent) or small-group ministry (41 percent), according to churchgoers.

Researchers also found few churchgoers say their church is hostile to mental health concerns. More than half (54 percent) say their church encourages counseling, while only 2 percent say their church discourages counseling. Twenty-one percent say their church has no opinion about counseling, while 23 percent aren’t sure of their church’s stance.

Twenty-six percent say their churches encourage the use of medications in treating mental illness. Six percent say their church discourages the use of prescription medications. Most say their church has no opinion about medications (37 percent) or are not sure what their church’s stance is (31 percent).

Pastors want to help

Most Protestant pastors believe their church is taking a proactive role in preventing suicide and ministering to those affected by mental illness, according to LifeWay Research.

While 80 percent say their church is equipped to assist someone who is threatening suicide, only 30 percent strongly agree, meaning more than two in three pastors acknowledge they could be better equipped.

While 80 percent say their church is equipped to assist someone who is threatening suicide, only 30 percent strongly agree, meaning more than two in three pastors acknowledge they could be better equipped.

“Suicide in our culture has for too long been a topic we are afraid to discuss,” said Tim Clinton, president of the American Association of Christian Counselors. “Our prayer is that this research will start a national conversation on addressing the suicide pandemic in our nation, and we started by assessing the church’s perspective on and response to the issue. We need a clinically responsive approach that gives the gift of life back to those who feel filled with emptiness.”

Pastors say they are aware when suicides happen in their community. Sixty-nine percent say they know of at least one suicide in their community over the past year. And of those suicides, about four in 10 (39 percent) affected church members or their friends and families.

Ninety-two percent say their church is equipped to help family members when a suicide occurs. Pastors say their church springs into action, offering prayer (86 percent), calling (84 percent) or visiting with the victim’s family (80 percent) and providing meals (68 percent).

Churches also connect families with professional counseling (53 percent), help plan funerals (48 percent), connect the family with someone else who’s experienced a suicide in the family (44 percent) or provide other assistance.

A significant number of pastors also say they’ve been proactive in preparing to minister to those at risk of suicide. Forty-one percent say they have received formal training in suicide prevention, while 46 percent have a procedure to follow when they learn someone is at risk. Fifty percent say they have posted the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline number, 1-800-273-8255, where staff can find it.

Different views from pulpit and pews

Still, pastors are more likely to say their churches take a proactive role in preventing suicide than churchgoers are.

- 51 percent of pastors vs. 16 percent of churchgoers say their church has a list of mental health professionals who can treat those considering suicide.

- 46 percent of pastors vs. 12 percent of churchgoers say their church regularly addresses mental illness.

- 36 percent of pastors vs. 22 percent of churchgoers say their church has a lay counseling ministry.

- 29 percent of pastors vs. 23 percent of churchgoers say their church has a trained counselor on staff.

- 18 percent of pastors vs. 12 percent of churchgoers say their church has a crisis response team.

Reduce the stigma of mental illness and suicide

Clearly, churches want to be proactive in suicide prevention, McConnell said. They also are quick to respond to grieving families, he said. Still, there’s much work to be done to reduce the stigma of mental illness and suicide, McConnell said.

Ronald Hawkins, provost and founding dean of the School of Behavioral Sciences at Liberty University, said churches aren’t always a safe place for people to be vulnerable. According to the research, that seems especially true when someone is at risk for suicide.

He hopes the recent study will prompt churches to do more to prevent suicides.

“I and others in ministry have too often looked into the grief-stricken faces of those whose loved ones have taken their own lives,” Hawkins said. “If you have been there, your heart cry is, ‘Please, Lord no more.’ Yet it seems there are always more.

“Our research suggests that Christ-followers need to work harder at providing safe places, so filled with love and grace that trust can flourish. In such a place, those who have come to believe that suicide may be their only option may dare to open up their inner world and experience a reawakening of hope.”

The American Association of Christian Counselors, Liberty University Graduate Counseling program, the Liberty University School of Medicine, and the Executive Committee of the Southern Baptist Convention sponsored the study on suicide and the church. Researchers used a demographically balanced online panel for interviewing American adults.

Respondents were screened to include only Protestant and nondenominational Christians who attend worship services at a Christian church once a month or more. A thousand surveys were completed Sept. 15-19. Analysts used slight weights to balance gender, age, ethnicity, education and region. Those who had a close family member or close acquaintance die by suicide were oversampled (500 completed surveys) and subsequently weighted to be proportionate in questions applicable to all respondents.

The sample provides 95 percent confidence the sampling error from the online panel does not exceed plus or minus 3.4 percent (this margin of error accounts for the effect of weighting). Margins of error are higher in subgroups.