Orphan study transforms implementers

ATLANTA, Ga. (ABP)—Participants in the Journeys of Faith project are learning to rethink their beliefs about orphan care, especially in far-flung lands where orphanages have been the go-to solution.

Organizers say the initiative is raising awareness that the orphanage model isn’t always the best way to care for abandoned and other at-risk children in Third World nations.

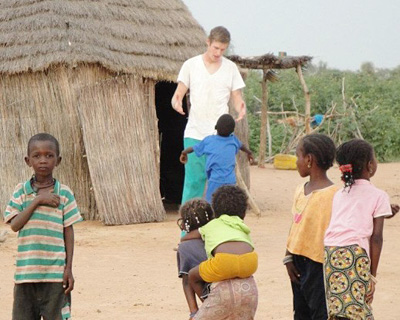

Ryan Carter, now a member of Peachtree Baptist Church in Atlanta, is embraced by a child during a mission trip. (Photo courtesy of Ryan Carter)But the ongoing study’s designers say they’re also finding seminary students and others tapped to recruit participants, as well as those who facilitate congregation-level small-group discussions, are experiencing new awareness around the issues.

Ryan Carter, now a member of Peachtree Baptist Church in Atlanta, is embraced by a child during a mission trip. (Photo courtesy of Ryan Carter)But the ongoing study’s designers say they’re also finding seminary students and others tapped to recruit participants, as well as those who facilitate congregation-level small-group discussions, are experiencing new awareness around the issues.

“This opened my eyes,” said Ryan Carter, a member of Peachtree Baptist Church in Atlanta and Journey of Faith facilitator for the congregation.

Carter is no stranger to shifting paradigms in mission work. At 23, he is studying global Christianity at McAfee School of Theology after spending much of his childhood, teens and early adulthood on mission trips around the world. He dropped out of those trips after realizing they sometimes cause more harm than good.

Journeys of Faith reassured him he isn’t alone by revealing similar concerns exist around orphan-care ministry.

A journey away from traveling

“I am already on this faith journey that is taking me away from traveling, and I didn’t know that other people in other parts of international ministry are also struggling with the same thing,” Carter said.

Such “aha” moments have been par for the course across the 20 congregations that already have participated in the study, said John Derrick, a steering committee member and an architect of the study with Faith to Action, a consortium of nonprofits and other groups seeking new ways of providing orphan care globally.

John Derrick, an architect of the new study with Faith to Action, on a mission trip to Africa several years ago. (ABP Photo)“That’s probably been the dominant theme,” he said of Carter’s experience and those of many other church members who, like Peachtree Baptist, participated in the initial pilot study of 20 congregations and other religious groups.

John Derrick, an architect of the new study with Faith to Action, on a mission trip to Africa several years ago. (ABP Photo)“That’s probably been the dominant theme,” he said of Carter’s experience and those of many other church members who, like Peachtree Baptist, participated in the initial pilot study of 20 congregations and other religious groups.

“From the focus groups and the facilitators we’ve heard repeatedly: ‘I’ve responded for years with what were good intentions. I thought I was doing good, but I am realizing there is a better way,’” said Derrick, who also serves as the facilitator for the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship’s Vulnerable Child Network.

While the study included congregations, campus and other groups from a variety of denominations, the majority were CBF churches, Derrick said. The Fellowship’s effort to seek better ways to serve populations in need made its database of churches an ideal starting point for the Journeys of Faith project.

Derrick said the effort to transform orphan care included a big push in 2012 to convince denominations and other larger institutions to rethink their strategies in this area. This year, the focus has been on the local church.

“It’s interesting and exciting to see what happens when it gets to that level,” he said.

Shift in thinking

The process has been monitored through participant surveys given before and after the study. They mainly show a shift in thinking on how best practices are evolving to continue caring for orphans without reliance on orphanages, Derrick said.

Practices include creating micro loans for villages to help strengthen local economies and establishing support for schools and other education efforts to relieve parents and communities of those expenses.

The idea is to let local leaders determine the best ways to prevent children from becoming orphans in the first place, and then for mission groups to come along side to support those initiatives, Derrick said.

In addition to churches, campus ministries and one retirement community participated in the study, Derrick said.

Kate RineyThe common message participants see and hear in case studies presented to them is that for 90 percent of children in orphanages, poverty—not the death or absence of family —puts them there, said Kate Riney, a McAfee student and the mobilizer responsible for recruiting study participants in the Southeast.

Kate RineyThe common message participants see and hear in case studies presented to them is that for 90 percent of children in orphanages, poverty—not the death or absence of family —puts them there, said Kate Riney, a McAfee student and the mobilizer responsible for recruiting study participants in the Southeast.

Riney, the managing editor of McAfee’s Tableaux Online magazine, was drawn to the project as part of her ongoing passion for the plight of human trafficking victims. Over the years, she has come to see how poverty issues overlap with trafficking, and now she’s seeing how orphan care—done well or poorly—can be part of that dynamic.

“This made me realize another way to strengthen families that can be pre-emptive and girls may never have to live on the streets,” Riney said. “That’s when I got into vulnerable children’s ministries and adoption and orphan care.”

Gaining those insights wasn’t easy at Peachtree Baptist, where the small-group discussions often revolved around strong and differing opinions on the nature of poverty and whether any changes are needed at all in orphan care, Carter said.

Participants discovered new ways of providing orphan care go beyond many Americans’ tendency to simply throw money at complex problems, he added. Some were genuinely surprised to hear that. “They thought that is the best” way to minister to orphans, he said.

“It’s easier to write a check than go and see where that check is going,” he said.