Posted: 11/16/07

Did the Bible’s bad girl get a bad rap?

By Heather Donckels

Religion News Service

WASHINGTON (RNS)—Few historical characters rival Jezebel for negative stereotypes. Today, “she’s a household word for badness,” one scholar said. Culturally, she’s portrayed as a brash, sexually provocative woman wearing too much make-up, another observed.

So in her new book, author Lesley Hazleton strives to set aside stereotypes and cultural images and show whom Jezebel, one of history’s most infamous women, really was.

“She was a magnificent, proud, powerful queen of Israel,” said Hazleton, author of the recently released book, Jezebel: The Untold Story of the Bible’s Harlot Queen. “She was anything but the harlot and the slut of legend.”

|

|

Jezebel was a Phoenician princess whose marriage to Israel’s King Ahab was one of political convenience. She ran into trouble with the prophet Elijah when she brought her many gods to monotheistic Israel.

After a 31-year reign, she died a gruesome death, pushed out of a window and trampled by horses, then eaten by dogs.

In today’s society, Jezebel practically means prostitute, an association Hazleton said springs from the “dismaying literalism” with which people have read an Old Testament metaphor.

Biblical authors, not unlike modern writers, knew they could get their readers’ attention by sexualizing their material, Hazleton said. And so, they used the term “harlot” to describe people who abandoned Israel’s God to pursue foreign gods.

Jehu, the man who killed Jezebel, forever linked the word “harlot” with her name when he asked her son: “What peace, so long as the harlotries of your mother Jezebel and her witchcrafts are so many?” (2 Kings 9:22).

Alice Ogden Bellis, a professor at Howard University School of Divinity and author of Helpmates, Harlots, and Heroes, a book about Old Testament women, agreed the writer’s metaphor has been dangerously misconstrued.

“The narrator is not accusing her (Jezebel) of any sexual impropriety,” she said.

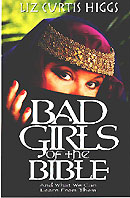

Hazleton’s book is the latest installment in a continuing trend of books focusing on the overlooked stories of biblical women. Liz Curtis Higgs wrote Bad Girls of the Bible in 1999, focusing on some of the not-so-nice women in the Bible.

She agreed Jezebel had a powerful personality and strong leadership abilities, but does not put the queen in such a good light in her book.

“Hers is a tragic story when you get right down to it, because she had so much potential,” Higgs said. “But she was working for the wrong God.”

And while Hazleton wrote her book to debunk centuries-long legends about Jezebel, Higgs had a different purpose.

“I write about the bad girls (of the Bible) primarily … to show the goodness of God, because he loves and uses his people even though they’re flawed,” she explained.

Bellis, meanwhile, wrote her book when she couldn’t find a textbook to use in her graduate school class on Hebrew women. Her work surveys the literature—academic, creative and sermonic—written about biblical women.

In the last 30 years, “most of the books written about women in the Bible have been written by women,” Bellis observed. And while some women wrote on this subject before the 1970s, she said most treatments were nonacademic.

The advent of birth control, though, combined with increased accessibility to higher education, launched women from the home into careers that allowed them to write scholarly works.

“Basically, the profusion of books on women in the Bible … has coincided with the women’s movement and the increasing numbers of academically trained female biblical scholars,” Bellis said.

Recent years have brought an “increased interest in historical women, period,” Higgs said. Women are interested in stories that have stood the test of time, she said.

As a Christian, Higgs finds herself inspired by stories of virtuous women. But as a human, the stories of the Bible’s “bad girls” intrigue her.

“They’re the ones I’m most like,” she said.

We seek to connect God’s story and God’s people around the world. To learn more about God’s story, click here.

Send comments and feedback to Eric Black, our editor. For comments to be published, please specify “letter to the editor.” Maximum length for publication is 300 words.