Posted: 4/13/06

|

(Photo by Sebastiao Sagado/AMAZONAS Images/RNS)

|

Rwandan genocide survivor

finds freedom in forgiveness

By Bob Smietana

Religion News Service

WASHINGTON (RNS)—A line from Christ’s model prayer—“forgive us … as we forgive”—haunted Immaculee Ilibagiza during the Rwandan genocide of 1994.

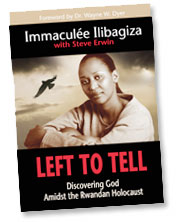

As she relates in her recently released memoir, Left to Tell, Ilibagiza was a 22-year-old university student visiting her family during the Easter holiday when a plane carrying Rwanda President Juvenal Habyarimana was shot down on April 6, 1994. His death sparked a “pandemic of violence,” Ilibagiza said.

“It was a disease, an epidemic of hate,” she said in an interview, and it took time to realize only forgiveness could bring healing. Ilibagiza’s parents, two of her brothers, and hundreds of her friends and neighbors—all Tutsis—were hacked to death with machetes by armed mobs of Hutus.

|

She found refuge in the house of a Hutu pastor, who hid Ilibagiza and seven other women in a tiny spare bathroom. A wooden wardrobe, slid in front of the bathroom door to hide the room’s existence, was all that stood between her and certain death.

In that small room, Ilibagiza—overcome with fear, anger and despair—began to recite prayers for hours at a time, asking God to spare her life. But every time she prayed the Lord’s Prayer, she stumbled. How could God ask her to forgive her family’s killers? She hated them with a “murderous passion” and wanted them to pay for what they’d done.

“In the early days of the genocide, if I had been given the opportunity to kill one of the killers, I think I would have,” she acknowledged.

The more she prayed, the more Ilibagiza realized she had been consumed by hatred, and she feared she was becoming just like the people who murdered her family.

“The hatred, it was so heavy,” she said. “When you feel you have to revenge them, to revenge your whole family, (it’s overwhelming). I don’t know how they live with themselves, the people who did this.” She felt as if God was asking her to “pray for the devil.” But the alternative— a life consumed by hate—seemed too much to bear. Out of desperation, and focused on the words of Jesus on the cross—“Forgive them, Father, for they know not what they do”—Ilibagiza began to pray that God would forgive her family’s killers.

“My heart is so heavy that it could crush me,” she wrote in her memoirs. “Touch my heart, Lord, and show me how to forgive.”

Forgiveness, Ilibagiza said, mostly is about letting go.

“If you believe enough to let go of hate—if you can say to God, ‘I am weak, I can’t do it’—that is enough,” she said. “God will do the rest.”

“Forgiveness has saved my life,” she said. “It’s a new life, almost like a resurrection.”

This sense of resurrection sustained her when it seemed that she faced certain death, Ilibagiza said. Several times mobs ransacked the pastor’s house, believing he was hiding Tutsis, but the hidden bathroom never was discovered.

After three months in hiding, and suffering from malnutrition, she and the other women eventually were rescued by French troops.

More suffering awaited Ilibagiza in a refugee camp. She had hoped her brother Damascence had escaped as well, but learned he had been cornered by a gang of thugs and hacked to death with a machete. One of the thugs sliced opened Damascence’s skull to look at his brain because Ilibagiza’s brother had a master’s degree. His killers had laughed about wanting to see inside the brain of a “smart Tutsi.”

Years later, Ilibagiza would visit one of her brother’s killers, a man named Felicien, in jail. The guard who took her to the cell expected her to curse Felicien. Instead, when she saw his face, and saw how a once-handsome young man had become a battered and emaciated prisoner, she took hold of Felicien’s hand and told him she forgave him.

When the guard asked her why, she said, “Forgiveness is all I have to offer.”

Ilibagiza, who now works for the United Nations in New York, visited Rwanda recently to film a documentary, Diary of Immaculee (www.diaryofimmaculee.com). She said she hopes her country “can learn to live again.”

“The people are still brokenhearted,” she said. “The country was broken on so many levels they don’t know where to start. … I feel an urgency to fix whatever I can.”

Ilibagiza said that before the genocide, she was never really sure if God exists. Now she knows, she said, and she believes God loves all people.

“If God is our Father,” she said, “that means he is suffering with us, with both the victims and the killers. Those people who killed in Rwanda are his children. If I am a good sister, I want to pray that they would be released from this evil, rather than cursing them to hell. I want people to hold onto God and to understand how big, how wide and how high God’s love is. It’s much bigger than we can understand.”

We seek to connect God’s story and God’s people around the world. To learn more about God’s story, click here.

Send comments and feedback to Eric Black, our editor. For comments to be published, please specify “letter to the editor.” Maximum length for publication is 300 words.